Cryptography Basics in 2026: Hashing vs Encryption (Explained for Beginners)

By Irene Holden

Last Updated: January 9th 2026

Quick Explanation

Hashing is a one-way “grinder” for integrity - producing fixed-length fingerprints like 256-bit SHA-256 or SHA-3 - while encryption is a reversible “locked tin” for confidentiality, typically AES-256 for bulk data with RSA/ECC or post-quantum ML-KEM/ML-DSA used for key exchange and signatures. For passwords, OWASP recommends slow, memory-hard functions such as Argon2id or bcrypt with unique salts, and always use vetted libraries and explicit permission when testing or experimenting.

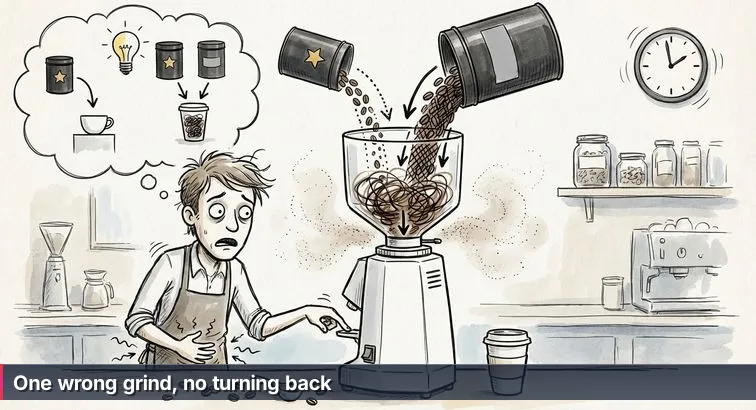

The grinder is already screaming before she realizes what she’s done. The last scoop of ultra-expensive beans disappears into the roar, instantly mixed with the cheap house blend. You can smell the coffee in the air now, but those beans are gone as beans forever. Right next to the grinder sit airtight, opaque tins of whole beans - silent, unlabeled to customers, but perfectly intact the moment someone with the key pops a lid.

Those are two completely different fates for the same coffee. One is a one-way transformation you can’t undo (once it’s ground, it’s ground). The other is the same beans, just hidden from view in a locked container. In cryptography, that’s the core metaphor: hashing is the grinder, and encryption is the locked tin. Hashing is about checking that what you have now came from the same original beans - this is data integrity. Encryption is about making sure nobody can see the beans until the right person unlocks the tin - this is data confidentiality.

| Metaphor | Crypto operation | Main goal |

|---|---|---|

| Grinding beans | Hashing (one-way) | Integrity: detect changes or compare originals |

| Locking beans in a tin | Encryption (two-way with a key) | Confidentiality: hide data but recover it later |

If you’re just starting in cybersecurity, this one picture - “grinder or locked tin?” - will show up everywhere. Job descriptions talk about using Argon2id for password hashing (that’s grinding beans in a safe way). The OWASP Top 10 lists Cryptographic Failures as a major web risk, which often comes down to confusing integrity and confidentiality, or using the wrong tool in the wrong place. Even NIST and CISA’s guidance on post-quantum cryptography standards is, at its core, about upgrading how we lock our tins without breaking everything built on top of them.

Industry explainers keep coming back to the same rule of thumb: encryption protects confidentiality; hashing protects integrity. The distinction is laid out clearly in resources like the Rippling guide on hashing vs encryption and an identity-focused explainer from Okta, both of which stress that hashes are deliberately one-way while encryption is meant to be reversible with a key.

As you read further, keep asking yourself the café question: am I grinding the beans just so I can recognize them again later (integrity), or am I locking the tin so only the right person can ever see what’s inside (confidentiality)? That simple habit, combined with ethical, standards-based cryptography, is what will make these concepts interview-ready instead of abstract theory.

What We Cover

- Grinder or locked tin? A simple crypto metaphor

- What problem does modern cryptography solve?

- How does hashing differ from encryption?

- How does encryption lock the tin?

- How does hashing grind data into fingerprints?

- How should passwords be stored in 2026?

- Where will you encounter hashing and encryption?

- Why does post-quantum crypto matter now?

- What common crypto mistakes should beginners avoid?

- How can beginners learn these concepts without drowning in math?

- Should I hash or encrypt? A quick decision checklist

- What should you remember from the coffee shop?

- Common Questions

If you want to get started this month, the learn-to-read-the-water cybersecurity plan lays out concrete weekly steps.

What problem does modern cryptography solve?

When you zoom out from the coffee bar to the whole internet, modern cryptography is really solving one big problem: how do we let data move and live everywhere without letting it be read, changed, or faked by the wrong people? Whether it’s a login request, a bank transfer, or a medical record, every serious security standard cares about the same three outcomes, often called the CIA triad. The Colorado State University System’s overview of cryptography, encryption, and hashing uses exactly this framework to introduce beginners to the field.

Those three problems are simple to state but tricky to solve at scale:

| Security goal | Plain-English meaning | Everyday example |

|---|---|---|

| Confidentiality | Only authorized people or systems can read the data | Your HTTPS banking session isn’t readable by anyone on the Wi-Fi |

| Integrity | Data can’t be changed silently; tampering is detectable | A software download fails verification if a single bit is altered |

| Authenticity | You can verify who actually sent the data | Your browser can prove it’s really talking to your bank’s server |

To hit those three goals, security engineers lean on three main cryptographic building blocks. Encryption protects confidentiality by scrambling data so only someone with the right key can read it. Hashing protects integrity by turning data into a one-way fingerprint that changes if the data changes. Digital signatures combine hashing with public-key cryptography so you can verify both who sent a message and that it hasn’t been modified. A learning resource from FlashGenius on encryption, hashing, and digital signatures walks through this same trio as the core of modern crypto.

Most real systems you’ll touch - TLS/HTTPS, VPNs, password storage, even blockchains - are just careful combinations of these three ingredients, arranged to keep confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity in balance. OWASP’s Top 10:2025 entry on Cryptographic Failures is full of examples where that balance breaks: passwords “encrypted” instead of hashed, data left unencrypted in transit, or signatures misused so authenticity can’t be trusted. As you keep reading, you’ll see how each piece maps back to the café: locking tins for confidentiality, grinding beans for integrity checks, and signing bags so everyone knows who roasted them.

How does hashing differ from encryption?

In the café, both the grinder and the tins start with the same thing - whole beans - but they do completely different jobs. When you grind beans, you’re changing them in a way you can’t undo. When you drop beans into a locked tin, you’re not changing them at all; you’re just hiding them from sight until someone with the key opens the lid. That’s exactly the split in cryptography: hashing is like grinding (a one-way transformation), and encryption is like locking a tin (a two-way process you can reverse with the right key).

Hashing: grinding beans you can’t un-grind

Hashing takes any input - “password123”, a log file, a whole disk image - and turns it into a fixed-length fingerprint called a hash. Same input, same hash every time; change even one bit, and you get a completely different result. But there’s no practical way to go backwards from the hash to the original data. That’s why guides like Splunk’s introduction to hashing in cryptography emphasize properties like being one-way and collision-resistant. In security terms, hashing is about integrity: you “grind the beans” so you can later check whether what you have now matches what you had before, without ever needing to reveal or recover the original.

Encryption: locking the tin with a key

Encryption also transforms data, but with a crucial difference: it’s designed so that someone with the correct key can reverse the process. You take readable data, combine it with a secret key, and get unreadable ciphertext. Later, the right key can decrypt it back to the original. As the team at Ping Identity explains in their comparison of encryption vs hashing vs salting, encryption protects confidentiality, because the goal is to hide data but still let authorized people open the “tin” and read it. That’s how HTTPS, VPNs, and disk encryption keep your traffic and files secret while still letting you use them normally.

"Encryption is reversible, while hashing is intentionally designed to be a one-way function."

- Ping Identity Blog, Encryption vs. Hashing vs. Salting

Key differences at a glance

| Aspect | Hashing (grinder) | Encryption (locked tin) |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | One-way - cannot feasibly recover original data | Two-way - can decrypt with the correct key |

| Main goal | Integrity - detect changes, compare equality | Confidentiality - keep data secret from others |

| Typical output | Fixed-length fingerprint (e.g., SHA-256 hash) | Scrambled data roughly similar in size to the input |

| Common algorithms | SHA-256, SHA-3, Argon2id, bcrypt | AES-256, RSA, ECC, ML-KEM |

When you’re designing or reviewing a system, the interview-ready question to keep in your head is: am I grinding the beans or locking the tin? If the system needs to prove data hasn’t changed - like file checksums or password verification - you want hashing and integrity. If the system needs to keep data hidden but still readable later - like secure messaging or database encryption - you want encryption and confidentiality. Resources such as the overview from Comodo’s hashing vs encryption explainer frame it the same way: use hashes when you never need the original back, and use encryption when you do.

How does encryption lock the tin?

Think of encryption as what happens the moment a barista drops rare beans into an opaque tin and snaps the lock shut. From the outside, you can’t see or smell what’s inside anymore, but nothing about the beans themselves has changed. In cryptography, encryption does the same for data: it keeps the contents intact but hidden, giving you confidentiality so only someone with the right key can “open the tin” and read what’s inside.

Symmetric encryption: one shared key for the tin

With symmetric encryption, the same secret key is used to encrypt and decrypt the data, like one metal key that every trusted barista shares for a particular tin. It’s very fast, which makes it ideal for protecting large amounts of data in transit or at rest. The global workhorse here is AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), and security guides consistently recommend AES-256 for strong protection. A deep-dive from Splashtop on how AES encryption works notes that AES is now used everywhere from government systems to remote access tools because it balances strong security with high performance. This “one key” style is what you see in full-disk encryption on laptops, VPN tunnels, and the bulk of an HTTPS session once it’s established.

Asymmetric encryption: public tins and private keys

Asymmetric encryption works differently: there’s a key pair. One key is public and can be shared widely (anyone can use it to lock a tin for you), while the other is private and must be kept secret (only you can open tins locked with your public key). Algorithms like RSA and ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) live here. RSA is the “old guard” and still widely deployed, typically with at least 2048-bit keys and often 3072-bit or larger for long-term security. ECC achieves comparable security with much smaller keys, which is why it’s popular for modern, mobile-friendly systems. A comparison from NetCom Learning on symmetric vs asymmetric encryption highlights that this public/private design enables secure key exchange and digital signatures over untrusted networks.

"Symmetric algorithms are preferred for encrypting large volumes of data, while asymmetric algorithms are mainly used for key exchange and identity verification."

- NetCom Learning Blog, Asymmetric vs. Symmetric Encryption

How they work together to secure the web

In real systems, these two styles are rarely used alone. Instead, they’re combined so each does what it’s best at. In a typical HTTPS connection, your browser uses the server’s public key (as part of a certificate and public key infrastructure, or PKI) to safely agree on a temporary symmetric key. After that, all your traffic is encrypted quickly with AES, using that shared secret. Resources like the CBT Nuggets guide to symmetric vs asymmetric encryption describe this as a hybrid approach: asymmetric encryption establishes trust and keys, symmetric encryption protects the actual data. For you as a beginner, the mental model is simple and interview-ready: asymmetric crypto is how we hand out and verify keys, symmetric crypto is how we lock the tin efficiently once everyone has the right key.

| Feature | Symmetric encryption | Asymmetric encryption |

|---|---|---|

| Keys | One shared secret key | Public key + private key pair |

| Main use | Fast encryption of bulk data | Key exchange, digital signatures, identity |

| Typical algorithms | AES-256 | RSA (2048-3072+ bit), ECC, ML-KEM for key establishment |

| Performance | Very fast | Slower, used sparingly |

How does hashing grind data into fingerprints?

When you pour beans into the grinder, you’re not hiding them; you’re transforming them. The sound kicks in, the smell fills the café, and what comes out is totally different in form. That’s what hashing does to data. It takes any input and “grinds” it into a short, fixed-length string that acts like a unique fingerprint. You can use that fingerprint later to check if you’re looking at the same “beans,” but you can’t realistically turn the grounds back into whole beans. In security terms, hashing is all about integrity, not confidentiality: you’re not locking a tin, you’re creating a consistent way to recognize data without ever needing to see the original again.

From data to fixed-length fingerprints

A hash function takes input of any size - a password, a log file, a 5 GB ISO image - and produces an output of a fixed size, such as a 256-bit value with SHA-256. The same input always produces the same hash, but changing even one bit of the input produces a wildly different output. Resources like the overview of hashing in Code Signing Store’s guide to the best hashing algorithms describe this as creating a “digital fingerprint”: compact, repeatable, and highly sensitive to changes.

Key properties that make hashes useful

Cryptographically secure hash functions are engineered with a few critical properties that make them safe building blocks:

- One-way: there is no feasible way to recover the original input from the hash.

- Deterministic: the same input always yields the same output.

- Avalanche effect: tiny input changes cause large, unpredictable changes in the hash.

- Collision resistance: it’s extremely hard to find two different inputs that produce the same hash.

"The best hashing algorithms are designed to be one-way functions that are fast to compute but infeasible to reverse or to find collisions for."

- Code Signing Store, What Is the Best Hashing Algorithm?

Modern hash algorithms in practice

In real systems, families like SHA-2 (for example, SHA-256) and SHA-3 are the workhorses for integrity checks and digital signatures. They show up when you verify a downloaded file’s checksum, when Git names a commit by hashing its contents, and when blockchains chain blocks together. Importantly, while quantum computing threatens some public-key algorithms, modern hash functions remain comparatively robust: as an analysis on MEXC’s article on quantum computing and crypto notes, quantum attacks like Grover’s algorithm only offer a quadratic speed-up against hashes, not the kind of total break seen with RSA or certain elliptic-curve schemes. That’s why, even as we upgrade how we “lock tins” with post-quantum algorithms, secure hashes continue to be trusted for integrity.

SHA-256 vs. SHA-3 at a glance

| Feature | SHA-256 (SHA-2 family) | SHA-3-256 |

|---|---|---|

| Output size | 256-bit hash value | 256-bit hash value |

| Design | Merkle-Damgård construction | Keccak sponge construction |

| Common uses | File checksums, digital signatures, blockchain | Alternative to SHA-2 where a different design is desired |

| Security role | General-purpose integrity protection | General-purpose integrity protection with a newer design |

How should passwords be stored in 2026?

Every time someone signs in to a site, they’re quietly trusting that the café in the background is handling their “beans” correctly. If an app stores raw passwords, it’s like leaving bags of labeled beans on the counter: the first thief through the door gets everything. Modern systems are supposed to pour those passwords straight into a special grinder instead. That grinder is a password hashing function, and its entire job is to turn your password into something that proves you know it, without ever storing the original. You don’t want a locked tin here; you want a one-way grind.

Why we hash instead of storing passwords raw

Well-designed systems never keep the actual password. Instead, they follow a simple pattern:

- You create a password.

- The server runs it through a password hashing function.

- The server stores only the hash (plus some extra data like a salt and settings).

At login, the server hashes what you type again and compares the result to the stored hash: if they match, you’re in; if not, access is denied. Even if an attacker steals the database, they get only the ground “coffee,” not the original beans. The OWASP Password Storage Cheat Sheet is very direct about this: passwords must be stored using dedicated password hashing functions, not reversible encryption, because the goal here is integrity-style verification, not confidentiality you can undo later.

Why SHA-256 alone isn’t enough

General-purpose hashes like SHA-256 are great integrity grinders for files, but they’re too fast for passwords. Attackers can point GPUs or ASICs at a stolen password database and try billions of guesses per second, hashing each guess with SHA-256 and checking for matches. To slow them down, modern password hashing algorithms are deliberately expensive: they take more time and, in the best case, more memory per guess. According to both OWASP and surveys of current practice like Psono’s article on the evolution of password hashing, Argon2id is considered the gold standard today, with bcrypt still acceptable where Argon2 isn’t available.

"Argon2id is currently recommended as the first choice for password hashing, with bcrypt, scrypt, and PBKDF2 as acceptable alternatives."

- OWASP Password Storage Cheat Sheet

| Algorithm | Speed by design | Memory-hard? | Recommended use in 2026 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHA-256 | Very fast | No | General integrity checks (files, messages), not raw password storage |

| bcrypt | Configurable, intentionally slow | Limited | Widely deployed, still acceptable for password hashing |

| Argon2id | Configurable, intentionally slow | Yes (memory-hard) | Current best-practice choice for password hashing |

Salts and good vs bad patterns

On top of choosing the right grinder, you also need to add a little randomness. A salt is a unique random value generated per user and stored alongside their hash. The basic process looks like this:

- Generate a new random salt when the user creates or changes their password.

- Compute something like Argon2id(password + unique_salt) with strong settings.

- Store the salt and the hash together in the database.

This defeats precomputed rainbow tables and ensures two users with the same password get different hashes. Guides such as Wallarm’s explainer on hashing vs encryption vs salting stress that each user must have their own salt, and that salts should never be reused across systems. The correct pattern is a slow, memory-hard function like Argon2id or bcrypt, plus a unique salt per password. The incorrect patterns are encrypting passwords with AES and keeping the key on the server, hashing passwords once with unsalted SHA-256, or expecting to “decrypt” a hash later. Once that grinder starts up, there’s no going back - you can only compare new grinds, never recover the original beans.

Where will you encounter hashing and encryption?

Once you start looking, you’ll see the grinder vs locked tin metaphor everywhere in real systems. Every login, every green padlock in your browser, every “verify checksum” note on a download page is the café playing out in software: sometimes the system is grinding beans with hashing to check integrity, and sometimes it’s locking tins with encryption to keep things confidential.

Logging in: hashes behind every password prompt

When you type a password into a website, you’re not supposed to be sending your “beans” to be stored in a labeled jar. The server should immediately run your password through a slow, secure password hashing function (like Argon2id or bcrypt) and store only the resulting hash and its settings. On your next login, it grinds what you typed the same way and compares the new hash to the stored one. If they match, you’re in; if not, access is denied. As training materials for entry-level exams like CompTIA Security+ explain, this is a classic integrity check: the system never needs to “open a tin” and see your original password, it just needs to confirm the grind matches.

Browsing with HTTPS: hybrid encryption plus integrity

Open a banking site and see https:// with a padlock, and you’re watching multiple cryptographic tools working together. First, your browser uses asymmetric encryption (public/private keys) to agree on a shared secret with the server. Then it switches to fast symmetric encryption like AES-256 to protect the rest of the session. Alongside that, hashes and message authentication codes ride on each message so any change in transit is detectable. An overview from Emeritus on encryption vs hashing points out that this mix is what gives you both confidentiality (nobody else can read your traffic) and integrity (nobody can silently alter it) in everyday HTTPS connections.

"Encryption keeps data private while hashing verifies that data hasn’t been altered; secure systems depend on using both in the right places."

- Emeritus Blog, Encryption vs Hashing

Downloads, updates, and software integrity

Whenever you download an operating system image or critical update and see a “SHA-256 checksum” on the vendor’s site, that’s a pure hashing use case. You download the file, run it through a hash function locally, and compare your result to the published hash. If one bit changed during download - whether from corruption or tampering - the hash will be completely different. Here, you’re not hiding anything; you’re verifying integrity by checking whether today’s “grounds” match the original beans the vendor published.

Messaging apps and VPNs: mostly locking tins

Modern messaging apps and VPN clients lean heavily on encryption. End-to-end encrypted messengers use protocols that combine public-key cryptography for key exchange with symmetric ciphers like AES for message content, so that only the sender and recipient devices can read the plaintext. VPNs do something similar at the network level, wrapping all your traffic in an encrypted tunnel. Hashes are still in the background to detect tampering, but from a user’s perspective these tools are about confidentiality: every packet is being sealed in a locked tin before it ever hits the wider network.

| Scenario | What you notice | Crypto under the hood | Main goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logging in to a website | “Password incorrect” or successful login | Password hashing (Argon2id, bcrypt) with salts | Integrity - does your input match the stored hash? |

| Browsing with HTTPS | Padlock icon, https:// in address bar | Public-key for key exchange, AES for data, hashes/MACs | Confidentiality + integrity for web traffic |

| Verifying a file download | Checking a published SHA-256 value | General-purpose hashing (SHA-256, SHA-3) | Integrity - has the file been altered? |

| Using a VPN or secure messenger | “Connected” status, unreadable traffic on the wire | Hybrid encryption (public-key + AES), integrity checks | Confidentiality - hiding content from intermediaries |

Why does post-quantum crypto matter now?

Imagine someone recording every time a barista locks a tin, planning to come back years later with a skeleton key that opens all of them at once. That’s the fear with quantum computing and today’s encryption: attackers can capture encrypted traffic now and wait until future machines are strong enough to break the locks. This “harvest now, decrypt later” idea is why post-quantum cryptography matters even to junior security folks. It’s not about making coffee stronger; it’s about upgrading the locks on our tins before a new kind of lockpick shows up.

What quantum computers actually threaten

Quantum algorithms pose their biggest risk to public-key encryption and digital signatures - the asymmetric “public tin/private key” systems like RSA and many ECC schemes that underpin TLS, VPNs, and software updates. If those get broken, the confidentiality and authenticity of past traffic and signed code can be compromised. By contrast, symmetric ciphers such as AES and modern hash functions like SHA-2 and SHA-3 are considered much more resilient; they may need longer keys or outputs, but they’re not wiped out in the same way. That’s why professional overviews, including Quantum Xchange’s look at post-quantum risks, frame the quantum shift primarily as a problem for the locks on tins (public-key crypto), not for the grinders (hashing) that give us integrity.

| Crypto type | Example algorithms | Quantum risk | Role in security |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical public-key | RSA, ECC | High - vulnerable to future large-scale quantum computers | Key exchange, digital signatures, certificates |

| Post-quantum public-key | ML-KEM, ML-DSA, HQC (backup) | Designed to resist known quantum attacks | Drop-in replacements for key exchange and signatures |

| Symmetric crypto | AES-256 | Moderate - may need longer keys, not fundamentally broken | Bulk data encryption (tins themselves) |

| Hash functions | SHA-256, SHA-3 | Lower - still considered robust when properly sized | Integrity and part of digital signatures |

NIST’s new post-quantum “lock designs”

To respond to this, NIST ran a multi-year competition to standardize algorithms that can replace or augment RSA and ECC. The first standards are now set: ML-KEM (formerly Kyber) for encryption and key establishment, and ML-DSA (formerly Dilithium) for digital signatures. In addition, NIST selected HQC as a fifth backup algorithm for encryption, as summarized in an industry brief on post-quantum cryptography compliance standards from SafeLogic. These new algorithms are meant to be the next-generation locks on our tins: you still get confidentiality and authenticity, but with designs that current quantum attack models can’t easily break.

What security teams are being told to do

Government agencies are no longer treating this as a far-off research problem. In a joint factsheet, the NSA, CISA, and NIST explicitly recommend that organizations start preparing now by inventoring where RSA and ECC are used, planning for hybrid deployments that combine classical and post-quantum algorithms, and prioritizing the most sensitive systems first. The NSA’s guidance on how to prepare for post-quantum cryptography frames this as a multi-year migration: you don’t rip out all the old tins at once, but you do stop installing new ones that will be easy to open in a decade.

For beginners, the practical takeaway is more about awareness and choices than doing math. Know that when you see RSA/ECC in designs, you’re looking at locks that will eventually need upgrading. Learn the names ML-KEM, ML-DSA, and HQC so they’re familiar in interviews. And above all, resist any temptation to “design your own post-quantum scheme.” Just as with classical crypto, the ethical, standards-based path is to use vetted libraries and follow published guidance; experimenting on live systems you don’t own or control is both unsafe and illegal, no matter how futuristic the algorithm sounds.

What common crypto mistakes should beginners avoid?

Cryptography mistakes usually don’t look dramatic at first glance; they look like one tiny shortcut in a codebase or a checkbox left at its default. But they’re a big reason OWASP’s “Cryptographic Failures” sits in the Top 10 web risks: a single wrong choice can turn strong math into paper-thin protection. For beginners, the goal isn’t to become a cryptographer overnight - it’s to avoid the loud “grinder starts up” moments you can’t undo, like storing passwords wrong or casually testing attacks on systems you’re not allowed to touch.

1. Encrypting passwords instead of hashing them

One of the most common beginner mistakes is treating passwords like sensitive files and “protecting” them with AES or another reversible cipher. It feels safer than plain text, but it’s the wrong mental model: passwords should be ground (one-way hashed), not locked in tins. If an attacker ever gets the encryption key, every password instantly turns back into readable text. Modern guidance instead calls for slow, attack-resistant password hashing like Argon2id or bcrypt, each with a unique salt per user. A survey of current practice from Bellator Cyber Guard’s overview of password hashing algorithms highlights these functions specifically because they’re designed to make large-scale guessing attacks far more expensive than with raw encryption.

2. Expecting hashes to be “decrypted”

Another easy trap is to treat hashes like a funny-looking kind of encryption and ask, “How do I decrypt this hash?” That question itself is a red flag. A proper hash function is a one-way grinder: the only practical way to “reverse” it is to keep guessing inputs until one produces the same output. That’s why we combine slow password hashing algorithms with techniques like salting - to make that guessing process as costly as possible. An explainer from The Engineering Author on encryption vs hashing stresses this exact distinction for beginners: encryption is built to be reversible with a key, while cryptographic hashes are deliberately constructed so the original input can’t be feasibly recovered.

3. Rolling your own crypto or clinging to outdated algorithms

Because crypto concepts are fascinating, many learners are tempted to invent their own ciphers or keep using algorithms they recognize from older tutorials. That’s dangerous territory. Real-world breaches still trace back to MD5, SHA-1, DES, or homegrown “XOR ciphers” that attackers can tear through. Your job in most security roles is not to design new grinders or locks; it’s to pick the right, well-vetted ones and configure them correctly.

| Pitfall | Example | Safer modern choice | Why it’s risky |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using broken hashes | MD5, SHA-1 for new systems | SHA-256, SHA-3 | Known collision attacks make integrity checks unreliable |

| Using obsolete ciphers | DES, 3DES, short-key ciphers | AES-256 | Small key sizes and design flaws enable practical attacks |

| “Rolling your own” crypto | Custom block cipher or protocol | Standard libraries and protocols (TLS, vetted libs) | Subtle design bugs can completely break security guarantees |

| Hard-coding keys | Secrets in source code or config | Dedicated key management solutions | Once leaked, every encrypted asset is compromised |

4. Ignoring legal and ethical boundaries

Finally, experimenting with crypto tools on the wrong targets is more than a “beginner mistake” - it can be a crime. Practicing password cracking techniques, trying to break HTTPS, or probing VPNs is only appropriate on systems you own or where you have explicit written permission to test. Introductory cybersecurity tutorials, such as the Cyber Security Tutorial from GeeksforGeeks, consistently pair technical content with reminders about authorization and laws for a reason. In professional environments, respecting scope, using only standard, vetted cryptographic libraries, and never pointing attack tools at unauthorized systems are baseline expectations. The irreversible “grinder sound” you want to avoid isn’t just a design mistake - it’s crossing a legal line you can’t easily un-cross.

How can beginners learn these concepts without drowning in math?

Many people hit cryptography and immediately picture walls of equations. In practice, most entry-level security work doesn’t start with math; it starts with good mental models (like grinders vs locked tins), then backs that up with small, repeatable labs. Your job is to understand what encryption, hashing, and signatures do, when to use each one, and how to configure real tools safely - not to derive algorithms from scratch.

Start with stories and mental models, not formulas

A helpful way in is to treat crypto like learning a new language: you listen and speak before you worry about grammar. Short explainers and visual courses that walk through confidentiality vs integrity using everyday examples are perfect for this. For instance, an online class such as Coursera’s Encryption and Cryptography Essentials course focuses on concepts and real-world use cases - like HTTPS and secure messaging - before it ever leans on math. Pair that with your own “grinder vs tin” questions as you read: is this topic about one-way recognition (hashing) or reversible secrecy (encryption)?

Learn by doing: labs, captures, and simple tools

Once the ideas feel familiar, the fastest way to make them stick is to see crypto in the wild. That might mean capturing a TLS handshake in Wireshark, checking a SHA-256 checksum on a Linux ISO, or using a password-hashing library in a tiny demo app. Hands-on security trainings emphasize this kind of practice for beginners; guides like The Knowledge Academy’s overview of cryptography techniques show simple, concrete exercises rather than abstract proofs. The key is to always stay on the ethical side: run attacks and experiments only against systems you own or have explicit permission to test, and stick to well-known libraries instead of trying to build your own ciphers.

Use structured paths so you don’t get lost

If you’re switching careers, a structured path can keep you moving without getting buried in side topics. A focused cybersecurity bootcamp like Nucamp’s Cybersecurity Fundamentals program, for example, dedicates 15 weeks (at about 12 hours per week) to core ideas such as the CIA triad, network defense, VPNs, and ethical hacking, all for around $2,124 when paid in full. You progress through three four-week courses - Cybersecurity Foundations, Network Defense and Security, and Ethical Hacking - with weekly live workshops capped at about 15 students, so you can tie hashing and encryption directly to tools like VPN clients, intrusion detection systems, and basic password attacks done under authorization.

| Learning path | Structure | Typical focus | Good for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guided bootcamp (e.g., Nucamp) | Fixed schedule, 15 weeks, live workshops | Foundations, hands-on labs, interview prep | Career changers who want accountability and a clear roadmap |

| Online course (e.g., crypto essentials MOOC) | Self-paced video + quizzes | Concepts like encryption, hashing, PKI | Building a mental model alongside other studies |

| Self-study (books + small projects) | Completely flexible | Deeper dives into topics you choose | Supplementing structured training, filling specific gaps |

Whichever route you take, aim for a blend: concept-first resources to lock in the difference between integrity and confidentiality, small labs so you can see hashes and ciphertext in real traffic, and a structured path that connects it all to entry-level certifications like Security+. That combination lets you talk confidently about “grinding vs locking” in interviews - without ever needing to write out the math behind AES or Argon2id.

Should I hash or encrypt? A quick decision checklist

When you’re staring at a design or a coding task, the fastest way to decide between cryptographic tools is to ask one simple question: does someone need to read this data later, or do I just need to recognize it? If someone must read it later, you’re locking a tin and you need encryption (confidentiality). If you only need to check that the data hasn’t changed or that two values match, you’re grinding beans and you need hashing (integrity).

Security guides aimed at practitioners, such as Training Camp’s encryption best practices overview, echo this rule: encryption is for protecting data in transit and at rest so it stays secret, while hashes are for verifying that what you received is exactly what was sent. You rarely choose them in isolation; real systems mix them, but at any specific point in a design you’re usually solving either a “who can read this?” problem or a “has this changed?” problem.

| Scenario | What you need | Hash or encrypt? | Typical 2026 choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storing user passwords | Verify users without ever seeing the original password | Hash (one-way) | Argon2id or bcrypt with a unique salt per user |

| Sending a message or file someone must read later | Hide contents from everyone except intended recipients | Encrypt (two-way) | AES-256 for data, with RSA/ECC/ML-KEM for key exchange |

| Checking if a file was modified | Detect any change, even by one bit | Hash | SHA-256 or SHA-3 for integrity verification |

| Proving who sent a document and that it’s unchanged | Authenticity + integrity together | Hash + encrypt a signature | Digital signatures using RSA/ECC/ML-DSA plus a hash |

| Protecting an entire disk or database | Confidentiality for data at rest | Encrypt | Symmetric encryption with AES-256 and solid key management |

As one practical write-up on the current landscape of hashing and cryptography notes, modern systems layer these tools rather than treating them as either/or: hashes “fingerprint” what you care about, while ciphers “lock” what must stay secret so that integrity and confidentiality reinforce each other. A good example is the kind of hybrid designs discussed in Medium’s overview of hashing and cryptography fundamentals, where TLS uses hashing for message integrity and encryption for confidentiality in the same protocol.

When in doubt, come back to the café: if the system ever needs the original “beans” back, you should be locking a tin with strong, standard encryption. If the system only needs to know whether today’s “grounds” came from the same beans as before, you should be grinding with an appropriate hash. That simple checklist, plus current best-practice algorithms like AES-256, Argon2id, SHA-256, and post-quantum options where required, will keep your designs aligned with how working security teams make these decisions.

What should you remember from the coffee shop?

Walking out of the coffee shop, the most useful thing to carry with you isn’t the smell of roasted beans; it’s that simple question: am I grinding the beans, or locking the tin? If you remember nothing else, remember this mapping: hashing is the grinder (a one-way transformation for integrity checks), and encryption is the locked tin (a reversible process for confidentiality). Hashes help you recognize data without ever needing it back; encryption hides data so the right people can read it later.

Right behind that, keep a short list of modern tools in your head like labels on café gear. For integrity, that means general-purpose hashes like SHA-256 or SHA-3, and for passwords specifically, slow, memory-hard functions like Argon2id or bcrypt. For confidentiality, think of AES-256 for bulk data, with public-key schemes such as RSA, ECC, or post-quantum options like ML-KEM and ML-DSA handling key exchange and signatures. Resources that track evolving recommendations, such as an industry guide to NIST’s finalized post-quantum standards, can help you keep those labels up to date as algorithms are added or retired.

Equally important are the “do not” signs taped above the counter. Don’t encrypt passwords when they should be hashed. Don’t expect to “decrypt” a hash. Don’t roll your own cipher or protocol when battle-tested libraries exist. And don’t aim security tools at systems you don’t own or have explicit permission to test; every ethical hacking guide, including practical walk-throughs like Psono’s explanation of password hashing evolution, pairs techniques with clear warnings about legal boundaries for a reason.

If you keep these habits - choosing the right operation (grind vs lock), picking modern, standard algorithms, and staying inside legal and ethical lines - you’ll be able to discuss cryptography comfortably in labs, interviews, and junior roles. You don’t need to design grinders or tins yourself; you just need to recognize which one the situation calls for, and use it the way the standards say. The math can come later if you want it; the mindset is what gets you hired.

Common Questions

What's the simplest way to tell hashing and encryption apart?

Hashing is a one-way “grinder” used for integrity (you can recognize data later but not recover it), while encryption is a reversible “locked tin” used for confidentiality (data can be decrypted with the correct key). Examples: SHA-256 produces a 256-bit hash, and AES-256 is a common reversible cipher.

When should I hash data and when should I encrypt it in real systems?

If you only need to verify or detect changes (password checks, file checksums), use hashing; if someone must read the data later, use encryption. In practice, passwords should use Argon2id or bcrypt with unique salts, while confidentiality uses AES-256 plus proper key management.

Can I decrypt a hash or recover the original input from it?

No - cryptographic hashes are designed to be one-way, so you can’t feasibly recover the original from a hash; attackers must guess inputs or use precomputed tables. Using per-user salts and memory-hard functions like Argon2id drastically raises the cost of guessing attacks.

How should passwords be stored in 2026 to stay secure?

Do not store raw or reversibly encrypted passwords; use a dedicated password hash like Argon2id (OWASP-recommended) or bcrypt with a unique random salt per account and tuned cost/memory settings. Avoid fast hashes like plain SHA-256 for password storage because GPUs/ASICs can test billions of guesses per second.

Is post-quantum cryptography something I need to worry about now?

Yes - mainly for public-key systems: NIST has standardized algorithms such as ML-KEM (Kyber) and ML-DSA (Dilithium) for key establishment and signatures, while symmetric ciphers (e.g., AES-256) and hash functions (SHA-2/SHA-3) are more resilient but may require larger sizes. Organizations are advised to inventory RSA/ECC uses and plan hybrid deployments to guard against 'harvest now, decrypt later' attacks.

If snapshots intimidate you, follow the tutorial on mapping lab networks and using snapshots to safely break and rebuild VMs.

If you want to learn network security fundamentals with clear metaphors and lab-friendly examples, this post maps concepts to a school floor plan.

Beginners can learn cyber risk fundamentals through the kitchen-table metaphor and simple starter templates.

Build confidence with the learn to map services and versions with -sV section in our guide.

Career changers can learn to analyze packet captures and document findings for a security portfolio.

Irene Holden

Operations Manager

Former Microsoft Education and Learning Futures Group team member, Irene now oversees instructors at Nucamp while writing about everything tech - from careers to coding bootcamps.