Ethical Hacking Roadmap 2026: From Fundamentals to Your First CTF

By Irene Holden

Last Updated: January 9th 2026

Quick Summary

Yes - follow this 6-month roadmap and, with about 10-15 hours per week, you can move from fundamentals to completing a beginner-friendly CTF and publishing a public writeup. The plan is month-by-month (Month 1: networking & ethics; Month 2: Linux & scripting; Month 3: guided labs; Months 4-5: semi-guided HTB and full-chain practice; Month 6: your first CTF + portfolio), uses safe lab platforms like TryHackMe/HTB/picoCTF, and recommends a host with roughly 8-16 GB RAM and 50+ GB free disk to run your VMs.

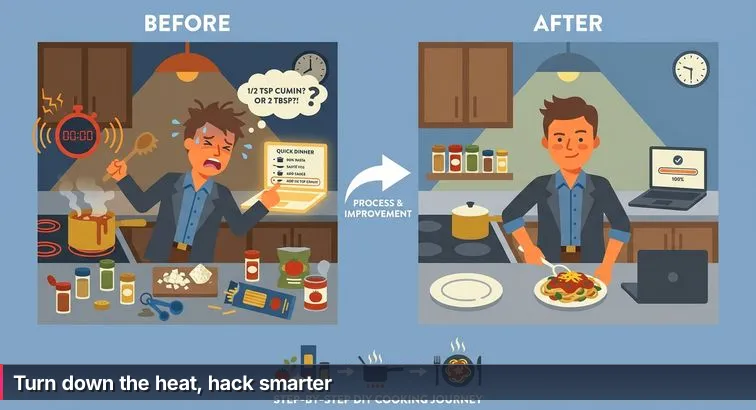

Think of this roadmap less like a random stack of recipes from YouTube and more like a 6-month menu plan. You’re not just collecting tools; you’re learning how to run a small kitchen: manage your time, keep things safe, and reliably plate one solid “dish” at the end - your first solved beginner CTF plus a clear learning history you can show to others.

What this roadmap is (and isn’t)

This plan is built to take you from zero to completing your first beginner-friendly CTF in about six months, assuming roughly 10-15 hours per week. Each step focuses on techniques - networking, Linux, scripting, a repeatable attack process - instead of dumping tool lists. That matches what experienced practitioners keep repeating in roadmaps like the TechGig ethical hacking career guide for 2026: employers hire people who understand systems, not people who can recite command flags.

“You must understand how a system works before you can break it.” - h7w, security researcher, From Zero to Ethical Hacker on Medium

This isn’t a certification cram plan or a bug-bounty get-rich-quick scheme. It’s closer to an apprentice schedule in a busy restaurant: you’ll start with knife skills (networking and Linux), move into simple dishes with a recipe (guided labs), then learn how to improvise a full course under time pressure (CTFs). At every stage, anything that touches a real system outside a lab is treated like food safety: you follow the rules or you don’t cook at all.

How to pace your 6 months

Your weekly commitment of 10-15 hours is the “medium heat” setting: hot enough to cook, not so high that you burn out. That typically looks like 5 short weekday sessions of 1-1.5 hours for drills, plus 1-2 longer 3-4 hour weekend blocks for labs. Career roadmaps like the Zero To Mastery ethical hacker path and other professional guides point out that consistent, moderate practice outperforms occasional marathons - very much like learning to control a stove instead of cranking everything to max.

If you go harder (20+ hours a week), you can compress parts of the plan; if you’re under 10 hours, expect it to stretch closer to a year. Either way, the way to “taste as you go” is to regularly pause and prove what you’ve learned: finish a room on TryHackMe, capture a packet in Wireshark and explain it, or write a few lines of Python to automate something simple. When frustration hits - and it will - treat that as a signal to turn the heat down and review the previous section rather than chasing a new tool or cert.

What each month focuses on

Each month has a main theme so you always know what you’re actually cooking:

- Month 1 - Foundations, Ethics & Networking: Set up a safe, legal lab, write your personal rules of engagement, and learn how the internet really works (TCP/IP, DNS, HTTP, ports) so later exploits have something to stand on.

- Month 2 - Linux & Scripting Basics: Get comfortable living in a Linux terminal and learn just enough Bash and Python to move files around, glue tools together, and understand simple exploit scripts.

- Month 3 - Guided Ethical Hacking Labs: Follow structured paths on platforms like TryHackMe or in a bootcamp so you can walk through full attack chains with training-wheels instructions.

- Month 4 - From Guided to Semi-Guided: Start tackling harder labs and beginner Hack The Box machines with fewer hints, using a consistent methodology instead of step-by-step recipes.

- Month 5 - Full-Chain Practice: Practice complete “box” workflows - recon → enumeration → exploitation → privilege escalation - until the pattern feels natural.

- Month 6 - Your First CTF + Portfolio: Enter a beginner-friendly CTF, solve at least a few challenges entirely within the event’s rules, and turn that work into a public writeup or GitHub repo you’d be proud to serve to a hiring manager.

As you move through the rest of this roadmap, treat each section like a course in a tasting menu: don’t skip around too much, don’t rush the cooking time, and never ignore the “health code” notes - staying inside legal labs and authorized environments is what lets you practice aggressively without burning your future career.

Steps Overview

- How to use this 6-month ethical hacking roadmap

- Prerequisites and lab setup

- Set your rules, goals, and safe lab (Week 1)

- Networking foundations: how the internet actually works (Month 1)

- Linux, command line, and beginner scripting (Months 1-2)

- Start guided ethical hacking labs (Month 3)

- Transition from recipes to techniques and methodology (Months 4-5)

- Prepare specifically for your first CTF (end of Month 5)

- Enter your first CTF and publish a portfolio piece (Month 6)

- Verification: how to know you’ve actually progressed

- Troubleshooting and common mistakes to avoid

- Common Questions

If you want to get started this month, the learn-to-read-the-water cybersecurity plan lays out concrete weekly steps.

Prerequisites and lab setup

Before you start “cooking” exploits, you need your mise en place: a safe lab, basic tools, and clear house rules. This isn’t busywork. A properly set up lab lets you try risky things without burning your day job laptop, and clear ethical boundaries keep you on the right side of the law from day one.

Set your non-negotiable legal rules

Think of legal and ethical constraints as food safety and health codes: professionals don’t argue with them, they build everything around them. Write down and follow rules like:

- I only test systems I own, control, or have explicit written permission to test.

- I treat any real data I see as confidential and never exfiltrate or share it without authorization.

- I only attack targets inside dedicated labs, CTFs, or bug bounty scopes with clearly written rules.

- I never scan random IP ranges or production sites “for practice.”

“Only hack systems you own or have explicit permission to test. Anything else isn’t ‘practice,’ it’s potentially a crime.” - u/0xS1gnal, contributor, r/tryhackme

Most cybercrime laws don’t care that you’re a beginner or that you “had good intentions.” Treat anything outside your lab like a restaurant treats raw chicken: it only goes where it’s supposed to go, handled with gloves, or it’s a violation.

Pick hardware and a host OS that won’t choke

You don’t need a gaming rig, but you do need enough resources to run virtual machines smoothly. Aim for at least 8 GB RAM (with 16 GB strongly preferred) and 50+ GB of free disk space. Any modern Windows, macOS, or Linux desktop can work as the host; the key is that you’re comfortable using it and keeping it patched and backed up.

Beginner roadmaps like the Coursera cybersecurity learning roadmap stress that you should avoid practicing directly on your main OS. Virtualization gives you a sandbox you can break and reset without touching your personal files, work accounts, or family photos.

Virtualization and guest OS: your main “practice kitchen”

Install a free hypervisor like VirtualBox or VMware Workstation Player, then create at least one Linux VM as your primary attacking box. For beginners, a general-purpose distro like Ubuntu is easier to learn; you can add tools as you go instead of being overwhelmed by Kali’s giant menu.

| Guest setup | Best for | Pros | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubuntu in VirtualBox | Day-1 beginners | User-friendly, huge community, easy updates | Security tools added manually (good for learning) |

| Kali Linux in VirtualBox | Once you know basic Linux | Preloaded with most offensive tools | Easy to “tool-rush” and skip fundamentals |

| Dual-boot Linux | Long-term daily Linux use | Full performance, no hypervisor overhead | Riskier to set up; not necessary for your first 6 months |

When you create your VM, give it 2 CPUs if available, 2-4 GB RAM, and at least 40-60 GB of virtual disk. Set networking to NAT so the VM shares your host’s connection but isn’t directly exposed to the local network. Then:

- Install Ubuntu or Kali from the ISO and apply all updates.

- Install guest additions (for better clipboard and display support).

- Take an initial snapshot named something like “clean-base-install” so you can always roll back if a future experiment trashes the system.

Create your core accounts and starter tools

With the lab ready, you need a few accounts so you can practice legally inside purpose-built environments. At minimum, create:

- A TryHackMe account for guided, beginner-friendly labs (its own team explains why it’s often better than Hack The Box early on in their TryHackMe vs Hack The Box comparison).

- A picoCTF account for beginner CTF challenges.

- A GitHub account to store notes, scripts, and later your CTF writeups.

- A password manager (e.g., Bitwarden, 1Password) to generate and store strong, unique passwords for all of the above.

From this point on, anything “hacky” you do lives inside your VMs and these lab platforms. That separation is your equivalent of a professional kitchen’s prep area and serving line: cleanly divided, well-labeled, and safe to work in every day.

Set your rules, goals, and safe lab (Week 1)

Week 1 is all mise en place: you’re not flambéing anything yet, you’re clearing counter space, sharpening knives, and taping the house rules to the fridge. In practice, that means deciding what you will and won’t touch legally, blocking off time you can actually sustain, and getting a clean lab VM ready so every risky experiment stays in a sandbox.

Write your personal rules and concrete goals

Start by writing a one-page “rules of engagement” and pinning it in your notes. At minimum, commit that you will only run scans and exploits against systems you own or have explicit written permission to test, plus training platforms and CTFs with clear scopes. Anything else is like serving undercooked chicken to the public: intent doesn’t matter if someone gets hurt. Pair those rules with 1-2 realistic goals for the next six months (for example: “Finish TryHackMe’s Pre-Security path” and “Solve at least one beginner CTF challenge and publish a writeup”).

“Learn daily, hack daily, fail daily... and one day those regrets quietly turn into skills that make impossible things suddenly possible.” - Security coach, quoted in an ethical hacking roadmap on Medium

Block realistic time for Week 1 and beyond

Next, decide how often you’re actually going to “turn the burner on.” This roadmap assumes about 10-15 hours per week, which can look like five 1-1.5 hour weekday sessions for drills plus one 3-4 hour weekend block for labs. Career guides like the beginner cybersecurity roadmap from ECCU stress that consistent, smaller blocks beat occasional all-nighters. For Week 1, schedule at least three sessions: one for ethics and planning, one for installing your lab, and one for poking around in the VM so it starts to feel like your “workbench” instead of a black box.

Build your first safe lab and journal (step-by-step)

Your last job in Week 1 is to set up a safe kitchen where you can burn things without consequences and start a simple learning log. Keep all “hacky” actions inside this lab; treat the rest of the internet like a restaurant treats customer food storage: strictly off-limits without documented permission. Follow these steps:

- Install a free hypervisor such as VirtualBox or VMware Workstation Player on your main machine.

- Download an Ubuntu ISO and create a new VM with 2 CPUs, 2-4 GB RAM, and a 40-60 GB virtual disk; set networking to NAT so the VM shares your host’s connection without being directly exposed.

- Boot the VM from the ISO, install Ubuntu, then open a terminal and run

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -yto apply updates. - In your hypervisor, take a snapshot named something like clean-base-install so you can instantly roll back if a future tool or exploit breaks the system.

- Create a “Learning Journal” note or repo (many learners on r/CyberSecurityAdvice’s 12-month roadmaps use GitHub for this) and log what you did, what worked, and what confused you.

Pro tip: Any time you’re tempted to point a scanner at a real company, stop and ask, “Do I have written permission, or is there a dedicated lab for this?” If the answer is no, treat it like serving food off the floor: it’s simply not an option in a professional kitchen - or in an ethical hacking career.

Networking foundations: how the internet actually works (Month 1)

Month 1 is all about learning how the “stove” works before you start throwing exploits into the pan. Networking is the heat every attack rides on, and most solid roadmaps (like David Bombal’s widely shared ethical hacker roadmap) put it right at the start for a reason: if you can’t picture what happens to a packet, you’ll be copy-pasting tools blind.

What to actually learn this month

Instead of trying to memorize every port number, focus on a small set of concepts you can explain in your own words. By the end of Month 1 you should be comfortable with the OSI model (especially Layers 3-4), IP addresses and subnets, the difference between TCP vs UDP, and what protocols like DNS, HTTP/HTTPS, and SSH are doing for you. Guides like h7w’s “From Zero to Ethical Hacker” on Medium stress this same order: understand how the internet moves data, then worry about breaking things safely in a lab.

Daily command drills: low-risk “tasting” of traffic

Spend 10-15 minutes a day in your terminal, treating each command like a quick taste test rather than a full meal. On your host or Linux VM, practice:

ping google.comto see if you can reach a host and how long it takes.traceroute/tracertto watch the hops your traffic takes across the internet.nslookup example.comordig example.comto see how DNS turns names into IPs.curl http://example.comto fetch the raw HTML of a page.

At this stage you’re only “tasting” public endpoints the way any browser would; you’re not doing intrusive scanning. When you later move to tools like Nmap, keep scans strictly inside your lab or against platforms that explicitly allow it (TryHackMe, Hack The Box, CTF ranges) the way a pro kitchen keeps raw meat in a designated prep area.

See the packets: Wireshark and core tools

Once the basic commands feel less scary, install Wireshark in your VM and do a short capture while you load a web page or run nslookup. Apply simple display filters like dns, http, or tcp.port == 80 and match what you see to the commands you just ran. This is where the pantry starts to make sense: you can see which “shelves” (layers and protocols) are involved in a simple action like opening a site.

| Tool | What it shows | Example command | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ping | Basic connectivity & latency | ping 8.8.8.8 |

Check if a host is reachable |

| traceroute / tracert | Path your packets take | traceroute example.com |

See intermediate routers & hops |

| nslookup / dig | DNS name ↔ IP mapping | dig example.com A |

Debug name resolution issues |

| Wireshark | Full packet contents & metadata | Filter: http |

Inspect protocols and traffic details |

Your Month 1 milestone and common pitfalls

By the end of Month 1, you should be able to describe what happens - at a high level - when you type http://example.com into a browser, run ping, traceroute, and nslookup without constantly Googling flags, and open Wireshark to identify a simple HTTP request. The biggest mistake beginners report is trying to memorize OSI layers or port lists without ever watching real traffic; the second is jumping straight into heavy scanners on random IPs. Keep the “heat” low and controlled: stay in your lab, focus on understanding flows end to end, and treat every small success as another technique you can reuse when you start attacking boxes in Month 3.

Linux, command line, and beginner scripting (Months 1-2)

Linux and the command line are your knife skills. For the next month or so, most of your practice is just learning how to hold the knife properly: moving around the file system, slicing logs with commands, and writing tiny scripts that automate boring tasks. Almost every serious roadmap - including step-by-step guides on LinkedIn - puts “get comfortable with Linux and a bit of Python” in the first few months, because most security tools assume you’re at home in a terminal.

Build Linux muscle memory in the terminal

Plan on 20-30 minutes a day inside your Linux VM with no GUI crutches. Treat each session like chopping a bag of onions: repetitive on purpose. Focus on:

- Navigation:

pwd,ls -la,cd,find - Files and directories:

touch,mkdir,rm,cp,mv,cat,less - Permissions:

ls -l,chmod,chown,sudo - Users and processes:

whoami,id,ps aux,top,kill - Networking basics:

ip a,ss -tulpn,ssh user@host

Give yourself small tasks: “Create a lab directory with subfolders for notes, scripts, and logs,” or “Download a file with wget and move it into the right folder.” Offensive security checklists, like those referenced in the 2026 penetration testing roadmap on Hacklido, assume you can do all of this from muscle memory before you ever touch an exploit.

Learn Bash as your “glue” language

Bash is how you chain tools together quickly, like moving a pan from stove to oven without thinking. You don’t need to write 500-line scripts; you do need to:

- Use pipes and redirection:

|,>,>>,2>&1 - Create simple variables:

target=10.10.10.10thenping $target - Write tiny loops for repetitive tasks

Two practical mini-projects for Month 2:

- A ping sweeper: read a list of IPs from

targets.txt, ping each one, and print which hosts respond. - A quick log filter: use

grepandawkin a one-liner to count how many times an IP appears in a log file.

| Language | Main role | Example use | Learning focus (Months 1-2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bash | Shell + glue | Chain tools, parse output | Pipes, redirection, simple loops, variables |

| Python | General scripting | Write scanners, tweak exploits | Syntax, functions, files, HTTP requests |

Add just-enough Python for hacking

Python is where you move from “operator” to “problem-solver.” You’re not trying to become a software engineer; you want enough fluency to read and slightly modify exploit scripts, automate recon, and manipulate data. Roadmaps like the ethical hacking guide on LinkedIn and multiple Reddit threads point to beginner-friendly books and courses such as Python for Everybody and Automate the Boring Stuff as ideal starting points.

- Start with basics: types,

if/for, functions, lists, dictionaries. - Practice file I/O: read lines from a wordlist, write scan results to a file.

- Use libraries:

requestsfor HTTP, maybesocketfor simple TCP connections.

Good mini-projects: a script that fetches a URL and searches the HTML for a keyword, or a very small port scanner that checks a handful of ports on a host in your lab. Keep all of this inside your VM or approved platforms; running random scripts or scanners against production networks is like practicing knife skills on customers’ plates - in real environments, you only “cut” where you have explicit permission. By the end of Month 2, you want the command line to feel like your natural workspace and Bash/Python to feel like tools you can reach for without freezing, not magic incantations you copy from someone else’s recipe.

Start guided ethical hacking labs (Month 3)

By Month 3, you’ve sharpened your knives (networking, Linux, basic scripting). Now it’s time to cook from recipes: guided labs where the platform tells you what to try, in what order, and why it works. Platforms like TryHackMe, picoCTF, and others highlighted in the Parrot CTFs guide to learning platforms are essentially safe training kitchens - everything inside them is explicitly meant to be attacked, so you can push hard without crossing legal lines.

Pick your main guided platform for Month 3

For this month, make TryHackMe your “house cookbook” and follow its structured paths rather than bouncing randomly between rooms. Work through the Pre-Security path (if you’re brand new), then the Introduction to Cyber Security path, and start the Junior Penetration Tester path. Within those, rooms like “RootMe” and “Pickle Rick” are excellent full-chain practice: you’ll do recon, exploitation, and privilege escalation with guardrails. Treat every machine as if it were in a professional test kitchen: you’re allowed to experiment aggressively inside the scope of the lab, but you never point tools at targets outside the platform.

| Platform | Best use in Month 3 | Style | Guidance level |

|---|---|---|---|

| TryHackMe | Primary guided path (Pre-Security, Intro, Junior Pentester) | Virtual rooms with step-by-step tasks | High - lots of hints and explanations |

| picoCTF | Extra practice on focused challenges (web, crypto, forensics) | Jeopardy-style CTF challenges | Medium - hints, but fewer detailed walkthroughs |

| Parrot CTFs | Occasional events and alternative labs once basics are solid | Competitions plus training content | Varies - from beginner brackets to advanced |

“Hands-on, performance-based learning beats theory every time - your keyboard time matters far more than reading about tools.” - Parrot CTFs team, Complete Guide to Cybersecurity Learning Platforms

Optional: add a structured bootcamp for extra scaffolding

If self-paced labs feel like too much chaos in the kitchen, consider layering in a structured program alongside Month 3. Nucamp’s 15-week Cybersecurity Fundamentals Bootcamp is built for beginners and career-switchers and is split into three 4-week courses (Foundations, Network Defense, Ethical Hacking), with about 12 hours per week of total effort, including a weekly 4-hour live workshop. Tuition starts around $2,124, which is significantly lower than many traditional bootcamps, and the curriculum explicitly preps you for certifications like CompTIA Security+, GSEC, and CEH while you practice in authorized lab environments. Think of it as having a head chef and a brigade to keep you on pace while you’re also cooking from your own recipe books on TryHackMe.

Work through labs so you actually learn, not just finish

To get real value from guided labs, resist the urge to skim instructions just to grab flags. Instead, follow a simple pattern: first, read the task and predict what you’ll need (Nmap? directory brute force? basic SQLi?). Second, run the commands yourself and annotate them in your notes - what does each flag do, what changed in the output? Third, only copy-paste when you understand the step’s purpose. If you’re stuck, use hints rather than full walkthroughs; if you still can’t move, accept the “recipe” this time, then redo the room a week later without looking. And, as always, keep all scanning and exploitation inside these lab platforms or your own VMs. Treat anything else on the internet like a stranger’s kitchen: you don’t touch their stove, or their food, unless you have explicit, written permission to be there.

Transition from recipes to techniques and methodology (Months 4-5)

Months 4 and 5 are where you stop reading every line of the recipe and start cooking by feel. Labs give you fewer hints, Hack The Box starts showing up in the mix, and the real skill becomes knowing the pattern: how you move from “I have an IP” to “I understand this box” without someone whispering the next command in your ear.

Lock in a repeatable attack methodology

From this point on, treat every target the same way a pro kitchen treats every dish: prep, cook, plate, clean. In hacking terms, that’s a simple methodology you follow on almost every box:

- Recon: Identify the target, run an initial scan (for example,

nmap -sC -sV target-ip) to find open ports and services. - Enumeration: Dig into each service in detail (web directories, SMB shares, FTP, SSH configs, version numbers, etc.).

- Exploitation: Use what you’ve learned to gain your first foothold (a shell, a web login, an exposed file).

- Privilege escalation: Move from a low-privilege user to admin/root using misconfigurations, weak sudo rules, or vulnerable binaries.

- Loot / Proof: Grab the flag or proof file, and note what data you could have accessed in a real engagement.

- Cleanup: Close sessions, remove any test files you created where the platform’s rules expect that, and finalize your notes.

Rooms like “RootMe” and “Pickle Rick” on TryHackMe’s Junior Penetration Tester path are perfect for drilling this end-to-end flow until it feels automatic. A CTF roadmap on Medium makes the same point: once you see the pattern, most challenges stop feeling like magic and start feeling like variations on a theme.

“Don’t memorize solutions, memorize approaches. Every CTF box is different, but your process should look boringly consistent.” - Anuradha Ranaweera, security engineer, CTF Road Map for Beginners

Introduce Hack The Box without burning out

Hack The Box (HTB) is like moving from a teaching kitchen to a busier restaurant: fewer instructions, more ambiguity, same health code rules. According to learners comparing platforms on r/tryhackme, HTB feels noticeably harder and less guided than TryHackMe, which is exactly why it’s better as a Months 4-5 step, not Month 1. Start with the Starting Point machines, then move into the easiest “Tier 0” or “Easy” boxes only after you’re consistently finishing full-chain TryHackMe rooms.

| Environment | Guidance level | Best use (Months 4-5) | Common mistake |

|---|---|---|---|

| TryHackMe (guided paths) | High - tasks & hints | Refining methodology on known patterns | Ignoring explanations, only chasing flags |

| HTB Starting Point | Medium - some hints | First exposure to less-guided boxes | Overthinking simple misconfigurations |

| HTB Easy machines | Low - minimal handholding | Practicing full-chain attacks by yourself | Jumping to Hard/Insane and burning out |

On HTB and similar ranges, keep your tools strictly pointed at the VPN-connected lab networks defined by the platform. Treat those ranges like your designated prep area: you can make a mess there, but you never swing a scanner at arbitrary production IPs just because you’re “curious.”

Use walkthroughs like a coach, not a cheat sheet

Walkthroughs in this phase are like watching a chef handle a tricky sauce: useful, as long as you go back and stir it yourself. Give yourself a 60-90 minute timebox per machine. During that window, work through your methodology: recon, enum, exploit, privesc. If you stall completely, skim a partial walkthrough only far enough to see the next technique (for example, “use directory brute forcing with gobuster” or “enumerate SMB shares”). Then step away from the writeup, learn that tool or concept in isolation, and return to finish the box on your own notes.

The goal by the end of Month 5 isn’t to crush “Insane” machines; it’s to be able to root a handful of Easy HTB boxes and harder TryHackMe rooms while being able to explain why each step worked. Any time you feel the urge to jump straight to hints or spin up a new, flashier tool, that’s your cue to lower the heat, go back to your process, and make sure you can still walk calmly from recon to proof without someone else’s recipe in front of you.

Prepare specifically for your first CTF (end of Month 5)

By the end of Month 5, you’re moving from practicing in an empty kitchen to cooking for guests: a real CTF with a scoreboard and a clock. The goal now isn’t to learn every trick; it’s to prepare just enough that the first event feels like a tough workout, not a panic attack. That means picking the right beginner CTF, rehearsing under time pressure, and packing a small, reliable “knife roll” of tools instead of dragging your whole toolbox onto the counter.

Pick a beginner CTF and learn its “menu”

Start by choosing a CTF that’s explicitly labeled beginner-friendly and Jeopardy-style (lots of small, independent challenges). Good candidates include picoCTF events, seasonal beginner CTFs on TryHackMe (like Advent of Cyber), and rookie brackets run by Parrot CTFs. Roadmaps like the Ethical Hacking Roadmap 2026 on MindMap AI call out CTFs as a key milestone because they force you to integrate everything: networking, Linux, scripting, and problem-solving under time constraints. Once you pick an event, read the rules carefully: scope, allowed tools, how flags look, whether collaboration is allowed, and when you’re allowed to publish writeups. Treat those rules like a restaurant’s printed menu and health code rolled into one.

Rehearse under a timer and pack a minimalist toolkit

For a couple of weeks before the CTF, simulate the pressure in short sprints. Take a box like “RootMe” or “Pickle Rick” on TryHackMe and give yourself 90-120 minutes to get the flag with no walkthroughs, only your own notes and official docs. If you stall, note where (recon, web enum, privesc), then practice that slice in isolation. In parallel, assemble a lean toolkit you know well: a browser with dev tools and maybe a REST extension, nmap, a wordlist like rockyou.txt, a text editor, and your note-taking template. The point is not to have every gadget; it’s to have a few reliable “pans” you can reach for without thinking.

| CTF category | What it tests | Practice drill | Go-to tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web | HTTP, basic web vulns | Replay requests, find hidden params | Browser dev tools, curl |

| Forensics | File analysis, logs, PCAPs | Carve info from images/PCAPs | strings, Wireshark |

| Crypto | Encoding, simple ciphers | Recognize and decode formats | Python, online decoders (where allowed) |

| Misc | Logic, OS tricks | Identify file types, odd behaviors | file, hexdump, Linux CLI |

“CTFs are where everything clicks. They expose the gaps in your training and force you to build a method, not just memorize tools.” - Cyb3rT4ct1c14n-23, picoCTF competitor, Trickster walkthrough author

Treat CTF rules like a health code

When the event starts, your first action isn’t to fire up nmap; it’s to re-read the rules. Only attack IPs, URLs, or services explicitly in scope. Never run denial-of-service attacks, never try to hack other teams, and never pivot from the CTF environment into external infrastructure, even if you spot something tempting. That’s the food-safety line: CTF organizers are giving you a licensed kitchen to experiment in, but if you wander into the dining room with a blowtorch, you’re done. Staying strictly inside scope protects the event, your reputation, and your future in ethical hacking.

Enter your first CTF and publish a portfolio piece (Month 6)

Month 6 is when you finally cook for guests: a live CTF with a scoreboard, a clock, and other people in the kitchen. Your job now is twofold: show up to your first beginner CTF with a calm game plan, and then turn whatever you manage to cook - whether that’s one solved challenge or ten - into a portfolio piece you’d be willing to serve to a hiring manager.

Play your first CTF like a pro, not a tourist

Once you’ve picked an event (picoCTF, a seasonal TryHackMe CTF, or a Parrot CTFs beginner bracket), treat it like a short shift in a restaurant. Register early, then carefully read the rules: which IP ranges or URLs are in scope, how flags are formatted, what tools are disallowed (for example, denial-of-service tools), and whether you can work in a team. Platforms like picoCTF explicitly design challenges to be attacked, but everything outside their ranges is still off-limits - just like you don’t wander into another restaurant’s kitchen and start experimenting on their stove.

- Block dedicated time for the event (for a 24-hour CTF, aim for 8-12 focused hours in 2-4 chunks).

- Start with the lowest-point “easy” challenges to build momentum.

- Use a 30-40 minute timebox per challenge: if you’re not making progress, switch categories and come back later.

- Take meticulous notes as you go: commands, mistakes, screenshots, and what finally worked.

Throughout the event, keep the health-code mindset: only touch targets that the organizers explicitly list, never attack other teams, and never pivot from the CTF environment into unrelated systems. You’re proving you can be both creative and controlled in a live-fire environment, not that you can ignore the rules.

“Show employers what you can do, not just what you’ve studied. Concrete projects and labs speak louder than any bullet point.” - CompTIA Cybersecurity Career Blog, CompTIA

Turn raw CTF notes into a portfolio dish

After the CTF ends (and any writeup embargo is lifted), your next move is to plate what you just did. Pick one to three challenges you solved and turn your scribbled notes into a clear, beginner-friendly walkthrough: what the challenge description was, how you approached it, dead ends you hit, the final path to the flag, and how this would map to a real-world vulnerability or skill. Then publish it somewhere public - GitHub, a simple blog, or a detailed LinkedIn post - so you’re no longer just cooking for yourself. Career guides and certification roundups on sites like CompTIA’s ethical hacker resources consistently emphasize that hands-on evidence (labs, writeups, repos) is what makes you stand out next to a stack of similar-looking résumés.

| Platform | What you publish | Best use | Bonus signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| GitHub | Markdown walkthroughs, scripts, notes | Technical depth, reproducible steps | Shows version control and documentation habits |

| Personal blog | Story-style posts with images | Explaining complex ideas simply | Demonstrates communication to non-experts |

| Short recap with key screenshots and takeaways | Broadcasting progress to your network | Invites feedback, mentorship, and recruiter attention |

Redefine “success” for your first CTF

For a first event, success is not “I won.” Success is: “I solved at least one real challenge under time pressure, stayed 100% inside the rules, and produced a writeup someone else could learn from.” That one clean, well-explained beginner web challenge often says more about your future as an ethical hacker than silently suffering through a dozen half-finished hard problems. If you treat every CTF this way - play hard but legal, then publish something you’re proud to serve - you’ll walk out of Month 6 with exactly what most beginners don’t have: a concrete story that shows you can take fundamentals, operate in a live environment, and plate a finished, documented “dish” at the end.

Verification: how to know you’ve actually progressed

At the end of six months, the question isn’t “Did I watch everything on my playlist?” It’s “Can I actually cook a basic meal without burning the kitchen down?” In hacking terms: can you explain core concepts in your own words, operate comfortably in Linux, work through a box with a repeatable process, and show at least one public artifact of your work. Industry trend reports, like the top ethical hacking trends article from GSDC, keep hammering the same point: hands-on competence and demonstrable skills are what separate real practitioners from people who’ve just collected course completions.

Check your fundamentals

Your first verification is in your head, not your tool list. You should be able to explain, out loud and without notes, what happens when you type a URL into a browser, what the OSI model is roughly doing at Layers 3 and 4, and why TCP and UDP behave differently. In Linux, you should move around directories, manage files and permissions, and use ssh without constantly searching for the right flags. On the scripting side, you want to be able to write small Bash one-liners that chain tools together, plus short Python scripts that read input, make a simple HTTP request, and write useful output to a file. If you can “taste” your own understanding by solving small tasks like these, your base stock is ready.

Check your hands-on hacking

Next, look at what you’ve actually done with those fundamentals. A healthy Month 6 snapshot usually includes completing TryHackMe’s Pre-Security path and most of Introduction to Cyber Security, working through a big chunk of Junior Penetration Tester, and rooting several full-chain boxes (for example, “RootMe,” “Pickle Rick,” and a few comparable machines) without needing a step-by-step guide for every move. On Hack The Box, you should have cleared the Starting Point series and at least a couple of Easy machines, even if you leaned on hints. Finally, you should have played at least one beginner CTF and legitimately solved one or more challenges inside the event’s rules and time limits.

| Area | Baseline indicator | Stretch indicator | Next adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundations | Explain OSI, DNS, TCP/UDP; navigate Linux; write tiny scripts | Debug simple network issues and script small automations solo | If weak, revisit Month 1-2 drills before adding new tools |

| Labs & boxes | Pre-Security + most Intro to Cyber; a few full-chain rooms | Significant progress in Junior Pentester; several Easy HTB boxes | If stuck, redo known boxes focusing on methodology, not flags |

| CTF readiness | One beginner CTF played; at least 1 solved challenge | Multiple solves across categories (web, forensics, misc) | If none yet, schedule a beginner CTF in the next month |

Check your ethics and your public signal

Progress isn’t just what you can break; it’s how you behave while you’re breaking it. A solid self-check here: you’ve kept all scanning and exploitation strictly inside your own lab, training platforms, or clearly scoped events; you haven’t “practiced” on random production systems; and you understand that health-code style rule as non-negotiable. On the professional side, you should have at least one public artifact - a GitHub repo, blog post, or detailed LinkedIn writeup - where you walk through a lab or CTF challenge clearly enough that a beginner could follow it. That’s your first “dish” you’re willing to serve to guests, not just something you tasted alone in your own kitchen.

If there are gaps, adjust the heat - not the goal

If you can’t yet tick most of these boxes, it doesn’t mean you’ve failed the roadmap; it means you need to tweak the temperature. Maybe you raced through networking theory but freeze when you open Wireshark; maybe you can solve boxes with constant walkthroughs but can’t explain why a privilege escalation worked. In each case, turn the burner down: go back one month in the roadmap, redo a smaller set of labs slowly, and write out what’s happening in your own words. Verification isn’t a one-time final exam; it’s a habit of regularly tasting your own progress so you know when to add more spice, when to simmer, and when a skill is finally ready to plate.

Troubleshooting and common mistakes to avoid

Even with a solid roadmap, everyone hits the “smoke alarm” phase: too many tools, too many tabs, nothing working, and a creeping feeling you’re not cut out for this. That’s normal. The difference between people who quietly quit and people who end up in real security roles is less about talent and more about how they troubleshoot these ruts while staying inside the legal kitchen.

Tool-rushing and certification FOMO

This is the classic beginner mistake: installing Kali, grabbing every exploit framework you’ve heard of, and eyeing OSCP or CEH before you can reliably explain what DNS does. That’s like buying a sous-vide machine when you still burn scrambled eggs. Certification bodies themselves, like EC-Council in their “Is CEH worth it?” overview, stress that credentials add value only when backed by real hands-on skills. If your notes are full of tool names but thin on what packets or permissions you actually observed, turn the heat down and go back to networking, Linux, and scripting drills until you can honestly say you understand what your tools are doing.

| Mistake | What it looks like | Why it hurts you | Practical fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool-rushing | New tool every week, no deep understanding | You can’t improvise when defaults fail | Pick 3 core tools (nmap, Wireshark, a browser) and use only them for 2-3 weeks |

| Cert FOMO | Researching exams more than practicing labs | Shaky foundations, wasted exam fees | Set a rule: no exam booking until you’ve finished your first CTF + a full lab path |

| Copy-paste CLI | Running commands you don’t understand | Dangerous on real systems; you don’t learn patterns | Annotate each command in your notes: “what does this flag change and why?” |

| Scope drift | “Just testing” random sites or IPs | Legal risk; bad professional habit | Hard rule: only touch your lab, CTF ranges, or written-scope bug bounties |

Walkthrough addiction and blind guessing

Another trap is either living inside walkthroughs or refusing to look at them at all. One leaves you dependent on recipes; the other wastes hours stirring the wrong pot. A better pattern is structured help: give yourself a 60-90 minute timebox per box, follow your recon → enum → exploit → privesc process, and when you get stuck, use hints or partial writeups only to identify what technique you’re missing (for example, “I never enumerated SMB” or “I forgot to brute force directories”). Then you go study that one technique in isolation and come back to the box later without the guide. Pro tip: if you can redo a machine a week later from your own notes without peeking, the walkthrough served its purpose; if you can’t, you leaned on it too hard.

Burnout, stalls, and slipping on ethics

When everything feels overwhelming, the temptation is either to crank the burner to max (10-hour weekends, five new platforms, three Discords) or to walk away entirely. Instead, treat it like simmering: shrink your sessions, narrow your focus, and “taste” understanding with tiny wins. Signs you need to adjust include dreading the laptop, jumping between five half-finished rooms, or feeling tempted to “just try” a scan on a random production site. That last one is a red flag: practicing against systems you don’t own or have written permission to test is the food-poisoning equivalent in this field. Warning: the solution to frustration is always to retreat to safe, legal environments (your VM, TryHackMe, HTB, picoCTF) and smaller, clearer goals, never to push boundaries on real networks. When in doubt, step back one stage in the roadmap, slow down, and rebuild confidence on challenges you can finish cleanly and ethically.

Common Questions

Can I follow this roadmap and complete my first beginner CTF in six months?

Yes - if you commit roughly 10-15 hours per week you can reasonably reach a beginner-friendly CTF in about six months; pushing 20+ hours/week can compress the timeline, while under 10 hours/week may stretch it toward a year. The key is steady practice on fundamentals, guided labs, then progressively less-guided boxes.

What minimum hardware and lab setup do I need to follow this plan?

Aim for at least 8 GB RAM (16 GB strongly preferred) and 50+ GB free disk space, run a VM with VirtualBox or VMware and an Ubuntu guest (or Kali later), use NAT networking, and take an initial snapshot (e.g., “clean-base-install”) so you can roll back experiments. This setup keeps your host safe while letting you break and rebuild VMs freely.

What should I focus on during the first two months to build the right foundation?

Spend Month 1 on networking fundamentals (OSI Layers 3-4, TCP vs UDP, DNS, HTTP) with short daily drills (10-15 minutes) and Wireshark captures; spend Month 2 building Linux muscle memory and basic Bash/Python scripting with 20-30 minute daily terminal practice. Those skills let you later read and modify exploit scripts instead of blindly copy-pasting commands.

How do I stay legal and ethical while practicing offensive skills?

Only test systems you own, control, or have explicit written permission to test and restrict practice to sanctioned platforms (TryHackMe, HTB VPN ranges, picoCTF) or scoped bug bounties; never scan random IPs or production sites. Remember most cybercrime laws don’t excuse ‘good intentions,’ so treat scope rules as non-negotiable.

What counts as meaningful progress after six months and how should I showcase it?

Meaningful progress is being able to explain what happens when you type a URL, navigate Linux without constant Googling, write small Bash/Python scripts, root several full-chain lab boxes, and solve at least one beginner CTF challenge. Publish one to three clear writeups or a GitHub repo of your CTF/lab work so employers can see concrete hands-on evidence.

Wondering whether offense or defense fits your style? See our which is better: red team vs blue team overview for personality fit and pay ranges.

Want to dig into attack surfaces? Read the analysis of edge device and VPN vulnerabilities and mitigation strategies.

Career changers should consult the top certs for career switchers into cybersecurity to map skills to roles.

If you work in IT, our complete guide to social engineering in 2026 explains modern scams and defenses.

Use the best practical questions for encryption, OSI, and incident response in authorized labs to build credible examples.

Irene Holden

Operations Manager

Former Microsoft Education and Learning Futures Group team member, Irene now oversees instructors at Nucamp while writing about everything tech - from careers to coding bootcamps.