Top 30 Full Stack Developer Interview Questions in 2026 (With Answers)

By Irene Holden

Last Updated: January 18th 2026

Too Long; Didn't Read

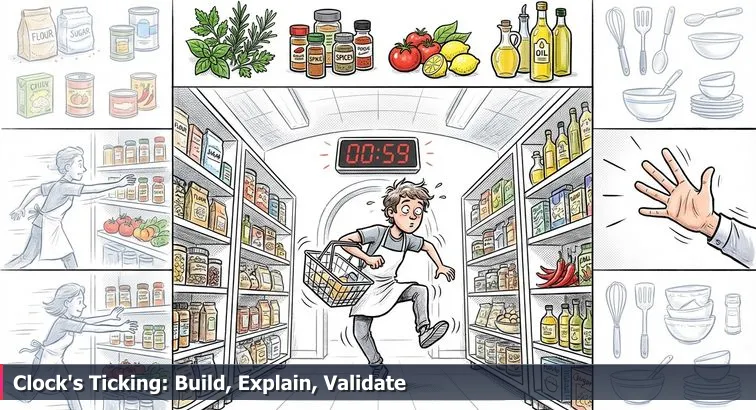

This article presents the top 30 full-stack interview questions for 2026 - the two standout picks are the JavaScript event loop (for reasoning about async behavior across front- and back-end) and AI-fluency (how you guide and validate AI outputs). Hiring trends now prioritize judgment under pressure - interviewers want clear explanations, tradeoff decisions, and the ability to spot AI-introduced errors - so treat this list as a “pantry map” to practice explaining concepts, choosing tradeoffs, and validating AI suggestions with tests and profiling.

The moment the pantry doors fly open on those cooking shows, the chefs who do best aren’t the ones who memorized the most recipes. They’re the ones who can look at a pile of ingredients, feel the clock ticking, and still decide, “With these things and this time, here’s what I’m going to make.” Full stack interviews work the same way now: a shared repo, a browser-based IDE, maybe access to an AI assistant, and a stranger watching while you figure it out in real time.

From memorizing recipes to knowing your ingredients

Lists like this “Top 30” can be comforting when you’re anxious or switching careers, but they’re not a magic script. As platforms like Karat’s engineering interview trends point out, companies have moved away from trivia and toward evaluating judgment under pressure: can you work through a real task, talk about tradeoffs, and adjust when something doesn’t work the first time? That means concepts like the event loop, React hooks, REST vs GraphQL, or JWT auth are less “answers to memorize” and more core ingredients you’ll recombine in lots of different dishes.

On top of that, AI is now on the table by default. Hiring managers know you’ve probably used Copilot, ChatGPT, or Claude to practice, and many interview guides, like the updated playbook on Dev.to’s AI-era interview prep, stress that your value is in how you guide and verify these tools - not whether you can type boilerplate from memory. In other words, you’re being judged less on whether you can write a JDBC query from scratch and more on whether you notice that the AI’s version forgot to parameterize inputs.

What interviewers are really testing now

Across the big categories in this list - JavaScript, React, Node/Express, databases, system design, DevOps, behavioral questions, and explicit AI-fluency - the pattern is the same. Interviewers are watching for three things: can you explain a concept in plain language, can you make a reasonable tradeoff with it (performance, security, simplicity), and can you spot when something that “looks right” (including AI-generated code) is actually subtly wrong. That’s the equivalent of tasting your dish before it goes to the judges, not just trusting the recipe card.

How to use this “Top 30” like a pantry map

To get real value from these questions, treat them as mise en place, not a script. For each one, your prep should look more like a practice kitchen than a flashcard deck:

- Explain the idea in your own words, as if you’re teaching a newer developer.

- Make at least one tradeoff decision with it (for example, when you’d choose SQL vs NoSQL, or REST vs GraphQL).

- Describe how you’d use an AI tool to help with it - and exactly how you’d double-check or test what the AI suggests.

Most importantly, keep your expectations honest: real interviews are messy, human, and now increasingly AI-augmented. You might get a system design prompt you’ve never seen, a React bug you don’t immediately understand, or an AI suggestion that sends you down a dead end. This list won’t prevent that. What it will do is stock your mental pantry with the ingredients that show up over and over, so when the clock starts and the “judges” start asking why you chose those flavors, you can plate an answer you actually understand - and not just something a model whispered in your ear.

Table of Contents

- Why these interview questions matter in 2026

- JavaScript event loop and task queues

- Closures in JavaScript

- Prototypal inheritance

- Temporal Dead Zone and let/const

- Debugging front-end performance

- Client-side, server-side, and static rendering

- Virtual DOM and React's rendering

- useMemo and useCallback

- Choosing Context, Redux, or Zustand

- Managing complex form state and validation

- Node.js concurrency model

- Express middleware for auth and logging

- REST vs GraphQL

- PUT vs PATCH

- JWT-based authentication

- SQL vs NoSQL trade-offs

- ACID properties and transactions

- How database indexes work

- Sharding and when to use it

- Data model for a social feed

- Designing a URL shortener

- Designing a real-time chat app

- Using caching like Redis to scale APIs

- What a CDN does

- API rate limiting strategies

- Basic CI/CD pipeline for full stack apps

- Why use Docker containers

- Effective Git workflows and code review

- Handling a shipped feature that went wrong

- Using AI tools and validating output

- Securing apps against XSS and SQL injection

- Approaching a 4-8 hour take-home assignment

- Bringing it all together

- Frequently Asked Questions

When you’re ready to ship, follow the deploying full stack apps with CI/CD and Docker section to anchor your projects in the cloud.

JavaScript event loop and task queues

When an interviewer asks about the JavaScript event loop, they’re not hunting for obscure trivia. They’re checking whether, under pressure, you understand why your “simple” async code sometimes fires in a weird order, or why a React state update seems delayed. This is one of those core ingredients: if you get it, you can reason about promises, async/await, and Node request handlers with a lot more confidence.

Single-threaded, but not stuck

JavaScript itself runs in a single thread, but the browser or Node runtime surrounds it with an engine that can juggle a lot of work. As guides like IGM Guru’s JavaScript interview series highlight, modern interviews almost always include at least one question on how the event loop works because it underpins async behavior across both frontend and backend.

The rough flow looks like this:

- Your synchronous code runs on the call stack until it’s empty.

- Async operations (timers, network I/O) are handled by the environment.

- When they finish, callbacks are queued as either macrotasks or microtasks.

- The event loop processes all microtasks, then one macrotask, then repeats.

That “microtasks first” rule is why a promise callback can run before a setTimeout(..., 0). In code:

console.log('A');

setTimeout(() => console.log('B'), 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('C'));

console.log('D');

// Output: A, D, C, B

Microtasks vs macrotasks at a glance

It helps to treat these like two different prep lines in the same kitchen - both handle callbacks, but with different priorities.

| Queue type | Common sources | When it runs | Typical impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microtask queue | Promises (.then/.catch/.finally), queueMicrotask |

After current call stack, before any macrotask | Great for follow-up work, but too many can starve rendering |

| Macrotask queue | setTimeout, setInterval, I/O callbacks |

After stack is empty and all microtasks are processed | Drives timers, I/O, and many Node callbacks |

This model matters in React (avoiding state updates that block paint) and in Node (keeping request handlers non-blocking). A number of full stack interview collections, like the ones compiled by LambdaTest’s full stack guide, explicitly call out the event loop as a must-know topic for debugging race conditions and performance issues.

Where AI helps - and where it quietly burns you

In practice, you might ask an AI assistant to “rewrite this callback hell with async/await” or “fix this promise chain.” That’s fine; it’s like asking a sous-chef to chop your vegetables. But without a solid event loop model, you won’t notice when the AI introduces a hidden problem, like firing an expensive microtask loop on every render or blocking the main thread with a big synchronous loop in a Node endpoint. Interviewers don’t just want you to recite “microtasks vs macrotasks” - they want to see you reason about why that promise runs before the timeout, and how you’d change your code when the heat turns up and things start executing out of the order you expected.

Closures in JavaScript

Closures are one of those ingredients that shows up in everything: callbacks, React hooks, event handlers, even simple utility functions. That’s why resources like InterviewBit’s full stack interview guide call closures out as a staple JavaScript topic: if you can explain them clearly under pressure, it tells the interviewer you actually understand how functions and scope behave, not just how to copy snippets from StackOverflow or an AI assistant.

A closure is what you get when an inner function “remembers” variables from its outer function’s scope, even after the outer function has returned. In other words, the function carries its lexical environment around like a backpack.

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function increment() {

count++;

console.log(count);

};

}

const counter = makeCounter();

counter(); // 1

counter(); // 2

Here, makeCounter runs once and returns increment. Even though makeCounter has finished, increment still has access to count via a closure, so it can keep and update state across calls without exposing count directly.

How closures show up in real apps

Instead of treating closures as a trick question, it helps to recognize the patterns where they actually earn their keep. Modern interview sets, like the ones cataloged in Coursera’s full stack interview questions overview, lean heavily on these practical uses:

| Use case | What the closure does | Real-world example | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation / “private” state | Hides variables inside a function scope | Counter or config object that can only be changed via specific functions | Helps you build modules with private state and clear APIs |

| Function factories | Pre-configures behavior based on outer arguments | makeLogger('info') that returns a function logging with a fixed level |

Lets you generate many small, specialized functions from one template |

| Async callbacks & hooks | Captures variables for later use when the callback fires | Event handlers, setTimeout callbacks, React hooks capturing props/state |

Critical for correct behavior in React hooks and async logic |

In React specifically, closures are everywhere: each render creates new functions that close over that render’s props and state. Understanding that is what helps you debug “stale state” bugs or realize why a hook is using an old value even though you’ve updated something elsewhere.

Common closure pitfalls (including with AI helpers)

Closures can quietly cause bugs if you’re not watching your scopes carefully:

- Capturing a loop variable incorrectly (for example, using

varin aforloop, so every callback sees the final value instead of the one per iteration). - Accidentally holding onto large objects in a closure, preventing them from being garbage-collected and causing memory leaks.

- In React, closing over stale props or state in event handlers or effects, leading to surprising behavior.

AI tools can happily generate code that uses closures without explaining them, or even introduce subtle closure bugs while “cleaning up” your callbacks. Your job in an interview (and on the job) is to read that AI-suggested code and ask: what variables is this inner function really closing over, will they have the values I expect when this runs later, and could this closure be keeping more data alive than it should? That ability to reason about closures is what shows interviewers you’re not just following a recipe - you actually understand the ingredients.

Prototypal inheritance

Under the hood, JavaScript objects aren’t just isolated bowls on the counter; they’re linked together in a chain that quietly shares behavior. That wiring is called prototypal inheritance, and it’s why you can call array methods on any [] you create or extend built-in types without copying code everywhere. Interviewers like the ones designing questions for platforms such as CodeSubmit’s full stack screens lean on this topic to see whether you actually understand how objects and methods work, or if you’re just hoping the framework handles it for you.

How the prototype chain actually works

Every JavaScript object has an internal link to another object called its prototype (often visible as proto in dev tools). When you access a property like user.greet, the engine:

- Looks for

greetonuseritself. - If it’s not there, walks up to

user’s prototype. - Repeats this process until it finds

greetor reachesObject.prototype.

That search path is the prototype chain. It lets objects share methods without duplicating them on every instance, which is both memory-efficient and conceptually simple once you see it in action.

| Pattern | How it uses prototypes | Pros | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain objects | Inherit from Object.prototype by default |

Simple syntax, great for configs and data blobs | Configuration, DTOs, simple maps of data |

| Constructor functions | Instances inherit from Fn.prototype |

Explicit sharing of methods across many instances | Older codebases, custom “classes” before ES6 |

| ES6 classes | Syntactic sugar over constructor + prototype | Familiar to OOP devs, cleaner syntax, extends support |

Most modern class-based models and components |

Constructors, classes, and the prototype object

Before classes, you’d often see something like this:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.greet = function () {

return Hi, I'm ${this.name};

};

const alice = new Person('Alice');

alice.greet(); // "Hi, I'm Alice"

Here, every Person instance shares the same greet function via Person.prototype. ES6 class syntax wraps the same idea in a more familiar shape:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

greet() {

return Hi, I'm ${this.name};

}

}

Underneath, methods defined in the class body still live on Person.prototype. Interview collections like the ones published by Braintrust for full stack roles often probe this point: they’ll ask how classes relate to prototypes, or how you’d add a method to all instances of a type without touching each object individually.

Why prototypal inheritance matters in interviews (and with AI)

This isn’t just academic. When a method is “mysteriously undefined” on one object but not another, or when this changes because a method was detached from its original object, knowing how the prototype chain works is what lets you debug calmly instead of flailing. It’s also what helps you reason about performance when you’re deciding whether to attach a method per instance or share it on the prototype.

AI tools will happily generate classes, factory functions, or even direct Object.create calls for you, but they won’t always explain the tradeoffs. In an interview, you want to be the person who can look at that generated code and say, “These instances all share their methods via the prototype, so memory usage stays low, but if we mutate the prototype at runtime, it will affect every existing instance.” That’s the difference between following a recipe and understanding the base sauce that ties the whole dish together.

Temporal Dead Zone and let/const

If you’ve ever sprinkled let and const into older code and suddenly started seeing ReferenceError before the line where you declared the variable, you’ve met the Temporal Dead Zone. Interviewers love this topic because it tests whether you really understand modern JavaScript semantics, not just the “old” var world. It also comes up a lot in curated question lists like Edureka’s full stack interview questions, right alongside closures and the event loop.

What the Temporal Dead Zone actually is

The Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ) is the period between entering a scope and the moment a let or const variable is declared. During that window, the variable exists in the scope but is uninitialized, and any attempt to access it throws a ReferenceError instead of quietly giving you undefined like var does.

console.log(x); // ReferenceError: Cannot access 'x' before initialization

let x = 5;

if (true) {

console.log(y); // ReferenceError

const y = 10;

}

This happens because let/const are still hoisted to the top of their block scope, but unlike var, they aren’t initialized until the actual declaration line is executed. The “temporal” part is about time (when the code runs), not about order in the file alone.

Why TDZ exists and where it bites you

The TDZ is there to catch bugs early. With var, a typo or re-ordering could silently turn into undefined and only blow up much later. With let/const, you get a clear runtime error right when you use a variable too early. It shows up in a few common patterns:

- Using a variable before its declaration in the same block.

- Default parameters that reference

let/constdeclared later in the function. - ES modules, where imports and exports also have TDZ-like rules.

function demo(a = value) {

const value = 42;

return a;

}

demo(); // ReferenceError: Cannot access 'value' before initialization

Modern interview guides like the ones compiled by UCD Professional Academy for full stack roles often use TDZ questions to see if you understand why switching from var to let/const isn’t always a drop-in refactor.

TDZ, refactors, and AI-generated code

AI tools are very keen on “modernizing” code: they’ll happily recommend turning every var into let or const, or reordering declarations to “clean up” a file. Without a solid mental model of the TDZ, it’s easy to accept those suggestions and end up with fresh ReferenceErrors in places that used to work. In an interview, being able to say, “If we move this let above where it’s used, or if we rely on it in a default parameter, we’ll hit the Temporal Dead Zone and get a runtime error” shows that you’re not just following a recipe - you understand how the language behaves when the heat is on.

Debugging front-end performance

Nothing turns up the heat in an interview like a front-end app that feels sluggish while someone watches you click around. This is where having a clear mental checklist matters more than remembering a single “trick.” Many real-world style interviews, including those built on browser-based environments like CoderPad’s full stack exercises, deliberately include subtle performance issues to see if you can stay calm, measure, and reason your way to a fix.

Start by measuring, not guessing

Instead of immediately sprinkling in useMemo or rewriting components, you want to reproduce the slowdown and gather evidence. That usually means:

- Identifying a concrete action that feels slow (navigating to a page, typing into a search box, opening a modal).

- Recording a profile in the browser’s Performance panel to see where time is going (scripting vs rendering vs painting).

- Running a quick Lighthouse check for page-level metrics like First Contentful Paint and Time to Interactive.

This “measure first” mindset shows interviewers you’re thinking like an engineer, not just randomly changing code. It also lines up with what hiring guides such as Indeed’s full stack interview prep describe as a key differentiator: being able to explain how you diagnose and validate performance work, not just claim that you “optimize React apps.”

Common bottlenecks and the right tools to spot them

Once you have a profile, you’re looking for the biggest, ugliest spikes first. Different categories of problems show different fingerprints, so it helps to map them to the right tools and typical fixes:

| Problem area | What you see | Tools to use | Example fixes |

|---|---|---|---|

| JavaScript runtime | Long “scripting” blocks, frozen UI during heavy work | Performance panel flame chart, React Profiler | Debounce handlers, move heavy loops off main thread, memoize expensive calculations |

| Rendering & layout | Frequent reflows, many component re-renders on each interaction | Performance panel (layout events), React Profiler | Split big components, avoid unnecessary state lifts, use React.memo judiciously |

| Network & bundling | Slow initial load, large JS bundles, many small requests | Network tab, Lighthouse, Coverage tab | Code-split routes, lazy-load rarely used components, compress and cache assets |

Working through this table out loud in an interview - “I’d check for render thrashing first, then look at bundle size” - shows you have a repeatable debugging recipe rather than just hoping you spot the bug by luck.

Letting AI assist without driving the car

AI can make this process faster, but it can’t replace the measuring step. You might paste a React Profiler screenshot or a performance trace into a tool like Claude or ChatGPT and ask, “What optimizations would you try here?” That’s a great way to brainstorm, as long as you still validate with fresh profiles and keep users’ experience as the judge. In an interview, be explicit about this: explain that you’d use AI to suggest potential fixes, then rely on DevTools and metrics to confirm what actually made the app feel snappier. That combination - structured diagnosis plus AI-accelerated experimentation - is exactly the kind of calm, under-pressure thinking hiring managers are looking for when the clock is ticking.

Client-side, server-side, and static rendering

Rendering strategy is one of those questions that shows up again and again in interviews: “Explain client-side vs server-side rendering,” or “When would you use static generation?” It’s like the judges asking why you chose to pan-sear instead of roast - same ingredients, different technique, different result. Being able to talk through CSR, SSR, and SSG calmly tells the interviewer you understand how your React code actually reaches the user’s screen, not just how to run npm start.

What CSR, SSR, and SSG actually mean

At a high level, all three approaches are answering the same question - where does the initial HTML come from? Modern prep resources, like Coursera’s full stack interview guide, highlight this trio as core concepts you should be able to compare, not just define.

| Strategy | Who renders the first view? | Typical use cases | Key pros / cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR (Client-Side Rendering) | Browser downloads a JS bundle and React builds the DOM | Authenticated dashboards, SPAs, internal tools | Pros: Very interactive, rich client logic, can offload work to browser. Cons: Slower first render, weaker SEO if bots rely on raw HTML. |

| SSR (Server-Side Rendering) | Server runs React, sends HTML which is then hydrated by the client | Public marketing pages, blogs, e-commerce product pages | Pros: Faster first contentful paint, better SEO, content visible without JS. Cons: More complex infra, increased server load per request. |

| SSG (Static Site Generation) | Build step pre-renders HTML files, served as static assets (often via CDN) | Blogs, documentation, mostly-static marketing sites | Pros: Very fast, cheap to host, highly cacheable. Cons: Not ideal for highly dynamic or personalized data; updates require rebuilds or ISR-style tricks. |

Frameworks like Next.js let you mix these: SSG for blog posts, SSR for product pages, and client-side fetching for user dashboards, all in one app. Interviewers are usually less interested in whether you know the labels and more in whether you can map a real product requirement to the right mix.

How to justify your choice to the “judges”

When you’re under interview pressure, treat this like explaining your cooking method to the panel. According to career guides like GSDC’s full stack interview playbook, the strongest answers don’t just say “I’d use SSR” but tie that choice to concrete constraints:

- SEO & first-load performance: Public, content-heavy pages often benefit from SSR or SSG.

- Personalization and data freshness: Highly personalized dashboards lean toward CSR or hybrid SSR + client fetching.

- Operational complexity: SSG + CDN is simpler to run than a cluster of SSR servers for a low-change marketing site.

- Team skills and stack: What your team already knows can be a valid part of the tradeoff.

In an interview, walk through these factors out loud: “Because this is a public product catalog with lots of search traffic, I’d default to SSR or SSG for the product pages, then layer CSR for cart interactions and account management.” That’s you plating the dish and explaining your technique.

Where AI fits into rendering decisions

AI tools can scaffold a Next.js app, wire up getServerSideProps or getStaticProps, and even suggest caching headers, but they can’t see your product goals. Your job - what the interviewer is actually grading - is to decide why you want SSR for this route and SSG for that one, then sanity-check that the AI’s code matches that intent. If you can comfortably explain how CSR, SSR, and SSG affect user experience, SEO, and operations, AI becomes a powerful sous-chef; without that foundation, it’s just throwing techniques at your app and hoping something tastes right.

Virtual DOM and React's rendering

React’s virtual DOM is one of those topics that sounds intimidating until you realize interviewers are really asking a simpler question: “Do you understand how React decides what to update on the page?” Because React is still the front-end “house spice mix” in so many jobs, resources like TestMu’s React interview question hub keep virtual DOM questions right near the top of their lists.

What the virtual DOM actually is

The virtual DOM (VDOM) is just a lightweight, in-memory representation of the real DOM. Every time your component tree “renders,” React builds a tree of plain JavaScript objects describing what the UI should look like. When something changes (props, state, context), React:

- Calls your components again to produce a new VDOM tree.

- Diffs the new tree against the previous one to find what changed.

- Computes the minimal set of operations needed on the real DOM.

- Batches and applies those updates efficiently.

This diff-and-patch cycle is what lets you write code as if you’re re-rendering everything on every change, while React only touches the parts of the real DOM that actually changed.

| Approach | How updates work | Strengths | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct DOM manipulation | Imperative calls like element.innerHTML = ... |

Fine-grained control, no framework overhead | Easy to create inconsistent state, hard to reason about as apps grow |

| React + Virtual DOM | Describe UI with components; React diffs VDOM and updates DOM | Declarative, predictable, easier to refactor; fewer manual DOM bugs | Some overhead for diffing; careless component design can still be slow |

| React optimizations (memoization, keys) | Help React skip parts of the tree or diff more accurately | Can significantly cut re-render work in large trees | Misuse adds complexity and can hide logic bugs |

When the virtual DOM helps - and when it doesn’t

The virtual DOM shines when you have lots of small, predictable updates: toggling items, updating lists, swapping views. But it’s not a silver bullet. Large, frequently changing trees, missing key props in lists, or heavy work inside render functions can still cause jank, even with the VDOM in play. That’s why guides like daily.dev’s full stack interview question set often pair “Explain the virtual DOM” with follow-ups about React.memo, proper use of keys, and how you’d profile a slow component tree.

Virtual DOM, AI, and your role as the “head chef”

AI tools are very good at churning out React components and even suggesting “optimizations” like sprinkling React.memo and useCallback everywhere. But without a solid understanding of how the virtual DOM and diffing work, it’s hard to tell whether those suggestions actually reduce DOM work or just make the code harder to understand. In an interview, you want to be able to look at AI-generated React code and say, “This memoization helps because it prevents unnecessary VDOM diffing in this subtree,” or, “Here it’s pointless; the component is cheap to render.” That ability to connect the abstract virtual DOM model to concrete performance decisions is exactly what convinces the “judges” you’re not just running recipes - you understand how the kitchen works.

useMemo and useCallback

For a lot of beginners, useMemo and useCallback feel like magical performance dust: sprinkle them around and hope the app gets faster. Interviewers know this, which is why they love asking, “When would you actually use these?” They’re not looking for a textbook definition; they want to see if you understand what these hooks do under the hood and when they genuinely help. Many full stack question sets, like Verve’s AI-powered interview prep, explicitly pair React hooks questions with follow-ups about performance and re-renders.

Two optimization hooks, two different jobs

Both hooks are about memoization, but they focus on different things:

| Hook | What it memoizes | Typical use case | When to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

useMemo |

The result of a calculation | Expensive derived data (filtered lists, computed layouts, heavy transforms) | When the calculation is cheap or runs rarely; memoization overhead outweighs gains |

useCallback |

The function reference itself | Stable callbacks for memoized children or hook dependencies | When children aren’t memoized and don’t care if the function identity changes |

So you might wrap a costly filter in useMemo:

const filtered = useMemo(

() => items.filter(item => item.matches(query)),

[items, query]

);

And you might wrap a handler passed to a memoized child in useCallback so the child doesn’t re-render unnecessarily:

const handleSelect = useCallback(

(id) => setSelectedId(id),

[setSelectedId]

);

When they actually move the needle

Strong answers connect these hooks to concrete situations instead of vague “optimization.” For example: a big dashboard where filtering thousands of rows causes jank on each keystroke, or a list component where every child re-renders on any parent state change. Interview-oriented guides like those from Second Talent’s full stack interview series recommend framing your answer around tradeoffs: you’d reach for useMemo only when a computation is measurably expensive, and useCallback when it actually reduces re-renders in a memoized subtree. That tells the interviewer you care about measured performance, not just sprinkling hooks because they exist.

Common mistakes (and how AI can nudge you into them)

The two big failure modes are overusing these hooks and using them incorrectly. Overuse clutters your code and can even hurt performance (every memoization has its own cost); incorrect dependencies can lead to stale values or effects that never re-run. AI assistants often suggest adding useMemo/useCallback “for optimization” without context, which can quietly introduce bugs or confusion. In an interview, you win points by pushing back: explaining that you’d first profile, then add these hooks only where they clearly prevent unnecessary work, and always with carefully chosen dependency arrays. That’s you showing you understand these hooks as precise tools in your toolkit, not seasoning you dump on every dish.

Choosing Context, Redux, or Zustand

Choosing between React Context, Redux, and Zustand is a classic “which tool do you reach for?” question. Interviewers aren’t grading you on brand loyalty; they want to see if you can match the tool to the problem, especially under pressure. Coaching-focused resources like IGotAnOffer’s full-stack interview coaching emphasize this point: your ability to justify a state-management choice often matters more than picking the same library the interviewer prefers.

Three tools, three kinds of problems

All three options move data around your React tree, but they shine in different situations. Think of them as different pans in the kitchen: each can cook, but some are better for quick sautés, others for big stews.

| Tool | Best for | Strengths | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| React Context API | Low-frequency, truly global data (theme, auth user, locale) | Built into React, no extra dependencies, simple mental model | Frequent updates can re-render all consumers; not ideal for large, fast-changing state |

| Redux (ideally Redux Toolkit) | Complex, shared state in medium/large apps with many interactions | Predictable data flow, great DevTools, strong ecosystem and patterns | More boilerplate and concepts; can feel heavy for small projects |

| Zustand | Lightweight global state without a big framework | Minimal API, less boilerplate, easy to adopt incrementally | Fewer built-in conventions and tools than Redux; patterns vary by team |

In a small app, you might keep most state local and use Context just for the current user and theme. As the app grows and you find yourself threading props through many layers or synchronizing related slices of state across distant components, that’s when a dedicated store like Redux or Zustand starts to earn its keep.

How to decide out loud in an interview

Strong answers walk through your decision logic instead of just naming a library. For example, you might say: you’d start with local state and Context, introduce Redux when many screens depend on the same data and you want time-travel debugging, or choose Zustand when you need a global store but want to avoid Redux’s ceremony. Articles on modern interviews, such as Swiftcruit’s breakdown of AI-era technical interviews, consistently note that hiring managers listen closely for this kind of tradeoff reasoning - they want to hear how you’d keep a codebase understandable for the next person, not just “what’s trendy.”

AI can wire it up, you still own the architecture

AI assistants are great at cranking out Redux slices, Context providers, or a quick Zustand store, but they don’t know your team size, app complexity, or performance constraints. In an interview, it’s perfectly fair to say you’d let AI help with the boilerplate, then you’d evaluate whether that choice is over-engineered (Redux for a three-page app) or under-structured (raw Context for a sprawling dashboard that re-renders constantly). That’s the signal the interviewer is looking for: that you treat Context, Redux, and Zustand as different ingredients you can reach for deliberately, not just whatever the last tutorial or AI suggestion happened to use.

Managing complex form state and validation

Complex forms are where a lot of otherwise solid beginners panic: multi-step wizards, conditional fields that appear and disappear, async “is this username taken?” checks, and a product manager who insists everything must autosave. Interviewers know this is real day-to-day work for full stack roles, which is why front-end heavy rounds often include at least one “build or debug this form” exercise, just like the practical tasks highlighted in resources such as Tech Interview Handbook’s full-stack prep guides.

Picking the right form tool for the job

You can absolutely manage form state with plain React state and onChange handlers, but once you add validation, error messages, and multi-step flows, a dedicated form library starts earning its keep. A lot of working React devs (and interviewers) expect you to at least know the names and tradeoffs of the common options.

| Approach / library | Strengths | Best use cases | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain React state | Minimal dependencies, full control | Simple forms, a few fields, basic validation | Quickly gets repetitive and error-prone with complex or multi-step forms |

react-hook-form |

Works with uncontrolled inputs, good performance, tiny bundle | Large forms, dynamic fields, scenarios needing fine-grained control over re-renders | API can feel low-level at first; you need to learn its registration model |

| Formik | Declarative, beginner-friendly, integrates well with schema validators | Forms where readability and clear structure matter more than micro-optimizations | Can re-render more often on huge forms if not configured carefully |

In an interview, you don’t have to swear allegiance to any single library. What matters is that you can say, for example, “For a multi-step signup with lots of validation, I’d reach for react-hook-form with a schema validator like Yup or Zod, to keep re-renders minimal and validation logic centralized.” That shows you know your tools and why you’d pick them.

Structuring complex state and validation

For anything bigger than a login form, it helps to think in layers:

- Shape your data first: Define a single source of truth for the form (an object that represents all steps and fields). Break that into per-step slices, but keep the overall structure clear.

- Centralize validation: Use a schema (Yup/Zod) that lives next to your form model, and plug it into your library so you’re not scattering validation rules across components.

- Handle async checks carefully: Debounce username or email-availability checks and guard against race conditions, so you don’t show “available” based on an earlier, now-outdated response.

- Wire in UX and accessibility: Focus/scroll to the first invalid field, associate errors with inputs via

aria-describedby, and make sure keyboard users can navigate multi-step flows.

This kind of layered explanation lines up with what experienced interviewers describe in resources like DataCamp’s interviews-with-engineers series: they’re less impressed by clever one-liners and more by candidates who can talk through how they’d keep a complex form reliable and humane for real users.

Letting AI scaffold without skipping the hard parts

AI tools are genuinely useful here. You can ask them to generate a starter react-hook-form setup, a Yup schema, or some boilerplate for multi-step navigation. But in an interview, your value is in everything the AI doesn’t reliably cover: making sure validation messages are clear, ensuring async checks don’t flicker or lie, keeping re-renders under control, and wiring accessibility correctly. When you talk through complex forms, mention that you’d happily use AI to save typing, then emphasize how you’d still design the data model, validation strategy, and user experience yourself. That’s what convinces the “judges” you can run the kitchen, not just follow whatever recipe your tools hand you.

Node.js concurrency model

Node’s concurrency model is one of those topics that sounds like a trick riddle: “If Node.js is single-threaded, how can it handle thousands of requests at once?” Interviewers love this question because once you really get the answer, you stop writing code that blocks the whole server without realizing it.

Single-threaded JavaScript, concurrent system

In Node, your JavaScript runs in a single main thread, but it’s wrapped in an event-driven runtime. The core idea is that you keep your own code short and non-blocking, and let Node’s event loop and underlying libuv layer delegate slow operations (like disk and network I/O) to the operating system or a small thread pool. That’s why guides like Turing’s Node.js interview questions list “How does Node handle concurrency?” as a must-know concept for backend and full stack roles.

At a high level, each incoming request schedules async work (DB calls, HTTP requests, file reads). Those operations run outside the main JS thread. When they finish, their callbacks get queued, and the event loop pulls them back onto the JS thread to run your logic. As long as your handlers avoid long, synchronous work, this model lets one process interleave progress on many concurrent requests without spinning up a thread per connection.

| Task type | Handled by | Best practice | What goes wrong |

|---|---|---|---|

| I/O-bound (DB queries, HTTP calls, file reads) | OS + libuv thread pool + event loop | Use async/non-blocking APIs (fs.promises, DB drivers, fetch/axios) |

Using sync APIs (e.g., fs.readFileSync) blocks the event loop for everyone |

| CPU-bound (heavy loops, encryption, image processing) | Main JS thread by default | Offload to worker threads, child processes, or separate services | Long CPU tasks freeze all other requests until they finish |

Common pitfalls and what interviewers listen for

In an interview, it’s not enough to say “Node is non-blocking.” You want to show you understand what that means in practice: avoiding synchronous file or crypto operations in request handlers, not doing big JSON parsing or tight loops on the hot path, and reaching for worker threads or background jobs when you do have CPU-heavy work. Many “why is this endpoint slow under load?” questions boil down to spotting exactly these mistakes in existing code.

AI assistants can generate a perfectly working feature that quietly uses fs.readFileSync, a blocking crypto function, or a huge in-memory loop inside an Express route. With a solid mental model of Node’s concurrency, you’re the one who says, “This will crush throughput under real traffic; we should switch to async I/O or offload this work.” That’s what interviewers are really testing with this topic: not just whether you’ve memorized the term “event loop,” but whether you can keep the kitchen running smoothly when a hundred orders hit the pass at once.

Express middleware for auth and logging

In Express, middleware is the conveyor belt your requests ride on. It’s how you plug in logging, authentication, validation, and error handling without rewriting the same logic in every route. Because Express is still one of the most common Node frameworks for full stack work, interview platforms like Prepfully’s full stack interview collections regularly include “explain middleware” questions to see if you really understand the request-response lifecycle.

What middleware is and how it flows

In Express, middleware is just a function with the signature (req, res, next). Each piece can:

- Read or modify the request (

req) and response (res) objects. - Decide to end the response (e.g., send JSON, redirect, return an error).

- Call

next()to hand control to the next middleware in the stack.

A simple logging middleware looks like this:

app.use((req, res, next) => {

console.log(${req.method} ${req.url});

next();

});

Every incoming request passes through this logger before it hits your actual route handlers, which is exactly what you want for cross-cutting concerns like logging and auth.

Common middleware types and where they fit

Interviewers often ask you to sketch out how you’d wire logging, auth, and validation together. Thinking in terms of middleware layers makes this easy to explain.

| Middleware type | Role in the pipeline | Typical placement | Key concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logging | Record requests, response codes, timing | Global app.use near the top |

Low overhead, avoid logging sensitive data |

| Authentication | Verify identity (e.g., JWT, session) | Global or on protected route groups | Token parsing, error handling, attach user info to req |

| Validation | Validate body, params, query | Per-route or per-router before handlers | Return clear 4xx errors, keep schemas centralized |

| Error handling | Catch thrown errors and format responses | At the very end, with signature (err, req, res, next) |

Avoid leaking stack traces in production, log appropriately |

JWT auth as a concrete example

For authentication, a common pattern is a JWT middleware that runs before protected routes. It extracts the token (often from the Authorization header), verifies it, and attaches the user payload to req.user if valid, or returns 401 if not. You might then stack role-checking middleware on top for admin-only routes. Full stack question sets like the Node/Express section in Scribd’s MERN interview compilation routinely probe this end-to-end understanding: not just “what is JWT,” but how you’d wire it through middleware across your API.

Letting AI scaffold, keeping security and performance in mind

AI tools are great at spitting out starter middleware for you: a basic logger, a JWT verifier, even a validation wrapper around a schema library. But they don’t automatically make the right calls about what to log, how to handle expired tokens, or how to avoid doing unnecessary work on every single request. In an interview, make it clear you’d happily let AI generate the boilerplate, then you’d review it for subtle issues: logging secrets, doing heavy work in global middleware, or sending overly detailed error messages in production. That review step is what shows you understand middleware as an architectural ingredient, not just copy-pasted sauce in every route.

REST vs GraphQL

REST vs GraphQL is one of those questions where the interviewer isn’t secretly rooting for one side. What they really care about is whether you can look at a product’s needs, the team’s skills, and the system’s constraints, then explain which style fits better and why. Hiring trend reports, like the API- and architecture-focused analyses in Paychex’s breakdown of modern tech hiring, consistently note that employers are prioritizing this kind of architectural judgment over framework trivia.

Two API styles, different philosophies

Both REST and GraphQL move JSON over HTTP, but they make different trade-offs in how clients ask for data and how servers expose it. Understanding those trade-offs is the “why” behind your answer, and it’s what interviewers listen for when they ask you to design an API on the spot.

| Aspect | REST | GraphQL | Practical impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint style | Multiple resource-specific URLs (/users, /users/:id/posts) |

Typically a single /graphql endpoint |

REST organizes around resources; GraphQL organizes around a typed schema |

| Data selection | Server decides response shape; clients often over/under-fetch | Client specifies exactly which fields and relations it wants | GraphQL can cut round-trips and payload size for complex UIs |

| Caching | Leverages HTTP semantics (status codes, ETag, Cache-Control) |

Requires custom caching strategies (per-field or per-query) | REST is simpler for CDN and browser caching; GraphQL needs more infra work |

| Versioning & evolution | Versioned endpoints (/v1, /v2) or backward-compatible changes |

Schema evolves by adding fields/types; clients ask only for what they need | GraphQL can ease long-term evolution when many clients share the API |

When you’d reach for each in a real system

In an interview, you earn points by tying your choice to concrete scenarios:

- REST tends to fit well when you have clear, CRUD-style resources, strong caching needs (public APIs, static-ish content), or integration with lots of third parties that already understand REST conventions.

- GraphQL shines when you’re supporting multiple clients (web, mobile, partner apps) that all need different data shapes, or when your UI has complex nested data you’d otherwise fetch with many REST calls.

Career advice columns on modern interviews, such as the question strategy pieces in The Business Journals’ interview playbook, highlight this kind of answer: not “GraphQL is better,” but “Given this product’s constraints, I’d start with REST because… and I’d consider GraphQL later if we hit these specific pain points.”

Where AI helps and where your judgment matters

AI tools can generate both REST controllers and GraphQL resolvers quickly, even scaffold a typed schema or OpenAPI spec. But they can’t see your traffic patterns, client diversity, or caching requirements. In an interview, make it clear you’d use AI to speed up boilerplate, then you’d still decide, for example, that a public, cache-heavy product catalog should default to REST, while an internal analytics dashboard with lots of flexible querying might benefit from GraphQL. That’s the signal interviewers are looking for: you know both ingredients, and you can explain which one you’d cook with under real constraints.

PUT vs PATCH

When interviewers ask about PUT vs PATCH, they’re not just checking HTTP trivia; they’re testing whether you think carefully about contracts between clients and APIs. Many full stack prep lists, like InterviewBit’s full stack interview questions, include this because it reveals how you design and document real-world update endpoints.

Both verbs are used to update a resource, but they carry different expectations. A typical guideline is that PUT represents a full replacement of a resource’s representation, while PATCH applies a partial update. With PUT, the client usually sends the entire resource; missing fields may be cleared or reset. With PATCH, the client sends only the fields to change, leaving everything else untouched. In both cases, well-designed APIs try to keep these operations idempotent (sending the same request multiple times yields the same final state).

| Aspect | PUT | PATCH | Example impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intent | Replace the full resource | Modify part of the resource | PUT /users/123 with a full user object vs PATCH /users/123 with just {"email": "new@example.com"} |

| Payload | Usually requires all fields | Includes only fields that change | PATCH can reduce payload size on large resources |

| Idempotency | Defined as idempotent by HTTP spec | Can be idempotent if designed that way | Same PUT should always result in same state; PATCH should too if you avoid “increment” style ops |

| Client expectations | Server may treat missing fields as “clear this” | Server ignores unspecified fields | Misunderstanding this can cause accidental data loss |

In an interview, you might talk through a user profile example: using PUT /profile from a settings page that always submits the full form, versus PATCH /profile for inline edits where you only send a single changed field. Strong answers also mention documentation: you’d clearly state in your API docs how each verb behaves so clients don’t accidentally wipe fields they didn’t include. This kind of explicit contract-thinking matches what architecture-focused guides, such as the API design sections in LambdaTest’s full-stack interview hub, describe as key to evaluating mid-level developers.

AI tools can happily generate handlers for both verbs, but they won’t automatically pick the right semantics or warn you if your PUT implementation behaves like a partial update. In an interview, it’s worth saying that you’d let AI scaffold the route code, then you’d review it to ensure it matches your chosen behavior (full replacement vs partial), remains idempotent where possible, and is documented clearly for frontend and third-party consumers. That’s the difference between just knowing the vocabulary and actually designing an API your teammates can rely on.

JWT-based authentication

JWT-based authentication is one of those cross-cutting ingredients that shows up in almost every full stack interview: login pages, protected APIs, “remember me” checkboxes, mobile apps talking to Node backends. Even language-specific prep guides like Codegnan’s backend interview questions emphasize auth and security patterns because they’re so central to real-world systems. If you can walk through a JWT flow calmly, you signal to interviewers that you understand both user experience and security basics.

Walking through a typical JWT login flow

A solid interview answer usually starts with the high-level steps, then fills in the security details:

- User login: Client sends credentials (e.g., email and password) to a

POST /auth/loginendpoint over HTTPS. The server verifies the password (with bcrypt/Argon2, never plain text). - Token issuance: On success, the server signs a JSON Web Token with a secret or private key. The payload typically includes a user ID and maybe a role, not sensitive data like passwords.

- Token storage: The client stores the token - ideally in an HttpOnly, secure cookie to reduce XSS risk, or as a bearer token in memory if you’re carefully managing CSRF.

- Authenticated requests: Subsequent requests include the token (via cookie or

Authorization: Bearer <token>). An auth middleware verifies the token, attachesreq.user, and either callsnext()or returns401. - Logout/expiry: Tokens have an

expclaim. You can implement logout by clearing cookies or maintaining a revocation list/rotation strategy for higher security.

Describing this end-to-end flow out loud is exactly the kind of clear, “show your thinking” answer many full stack hiring guides now encourage candidates to practice.

Access tokens vs refresh tokens

Once you’ve covered the basics, interviewers often probe how you’d balance security with user convenience. That’s where short-lived access tokens and longer-lived refresh tokens come in.

| Token type | Typical lifetime | Where it’s used | Security / UX trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access token | Short (minutes to ~1 hour) | Sent on each API call (cookie or Authorization header) |

Limits damage if stolen, but requires refresh flow to avoid frequent logins |

| Refresh token | Longer (hours to days) | Used only to get new access tokens (e.g., /auth/refresh) |

Improves UX by keeping users logged in, but must be stored and rotated carefully |

In an interview, a strong answer might be: “I’d use a short-lived access token for API calls and a longer-lived refresh token stored in an HttpOnly cookie, with rotation on each refresh. That way, even if an access token leaks, it expires quickly, and compromised refresh tokens can be invalidated.”

Security hardening and the AI factor

This is also where you show you’ve thought beyond the happy path. You’d mention HTTPS everywhere, proper token verification (checking signature, issuer, audience, and expiration), and avoiding sensitive data in the JWT payload. You might call out CSRF protection when using cookies (same-site flags, CSRF tokens) and what you’d log (failed logins, suspicious refresh attempts) without exposing secrets.

AI tools can definitely help here: they can scaffold Express middleware that reads a bearer token, calls jwt.verify, and returns 401s on failure. But they won’t automatically set secure cookie flags, design a sane refresh strategy, or decide what claims belong in the token. In an interview, it’s worth saying you’d lean on AI for boilerplate, then personally review it for subtle issues like missing expiration checks or logging entire tokens. That’s the difference between just “using JWT” and actually owning the authentication story in a production app.

SQL vs NoSQL trade-offs

Choosing between SQL and NoSQL is one of those decisions that quietly shapes everything else in your stack: how you model data, how you join it, how you scale, and how painful certain changes are later. That’s why most serious interview guides, including full stack question sets like Indeed’s full stack developer prep, call out database selection and trade-offs as a core topic. When an interviewer asks you to “pick a database for this system,” they’re really asking if you understand these differences well enough to justify your choice.

Structured tables vs flexible documents

SQL (relational) databases like PostgreSQL and MySQL store data in structured tables with rows and columns. They enforce schemas and relationships via foreign keys and usually provide strong ACID guarantees (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) for transactions. That makes them excellent for domains where data integrity is critical: orders, payments, inventory, user accounts, reporting. You can write powerful JOINs and aggregations across tables, which is a huge win for analytics and complex queries.

NoSQL databases like MongoDB, DynamoDB, or Couchbase lean toward flexible, schema-less or schema-light designs. Data is often stored as documents (JSON-like objects) where each record can have a slightly different shape, or as key-value pairs. They’re designed to scale horizontally more easily, and they make it natural to store denormalized, nested data structures. That can speed up development and simplify reads for document-like data (for example, a blog post and its comments in one document), but it shifts more responsibility for consistency and relationships onto your application code.

| Aspect | SQL (Relational) | NoSQL (Document / Key-Value) | When it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schema | Fixed, enforced at the DB level | Flexible, often enforced in app code | Strict schemas help in regulated domains; flexibility helps in fast-changing products |

| Relationships | First-class via foreign keys and joins | Modeled via references or embedded docs | Heavy cross-entity queries favor SQL; simple aggregates favor NoSQL |

| Transactions & ACID | Strong, multi-row/multi-table transactions are standard | Support varies; some offer limited or scoped transactions | Money movement, inventory, and critical invariants usually need SQL-style guarantees |

| Scaling | Great vertical scaling; horizontal via sharding/replication | Often designed for easy horizontal partitioning | Very high write or read volumes may push you toward NoSQL or a hybrid |

How to explain your choice in an interview

In an interview, you rarely get points for “SQL is better” or “NoSQL is more modern.” You score by tying your answer to a concrete scenario. For an e-commerce platform with orders, payments, and complex reporting, you might argue for a relational database because you need joins and strong transactions. For a high-traffic activity feed or logging service, you might favor a document or key-value store that can handle large, denormalized records and simple lookups at scale. It’s also fair to mention hybrid approaches: relational for core business data, NoSQL for caching, search, or event logs.

Letting AI propose schemas while you own the trade-offs

AI tools are surprisingly good at suggesting initial schemas or even translating an entity diagram into either SQL DDL or MongoDB collections. But they don’t automatically understand your consistency requirements, reporting needs, or scaling constraints. In an interview, it’s worth saying that you’d use AI to speed up boilerplate and explore options, then decide yourself whether this feature really needs ACID transactions and normalized tables, or whether a flexible, denormalized document model is the better ingredient for the dish you’re cooking.

ACID properties and transactions

When interviewers bring up ACID, they’re really asking, “Can I trust you not to corrupt our data under pressure?” Transactions are the safety net that keeps money from disappearing mid-transfer or orders from getting stuck half-created. That’s why serious prep guides, like the database sections in GSDC’s full stack interview career guide, consistently highlight ACID properties as foundational knowledge for backend and full stack roles.

ACID is an acronym that describes the guarantees a transactional system aims to provide. You don’t have to recite the textbook wording in an interview, but you do need to be able to explain what each property means in plain language and how it keeps real-world operations safe.

| Property | Plain meaning | Concrete example | Bug it prevents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomicity | All steps of a transaction succeed, or none do | Transferring money: debit one account and credit another in a single transaction | Money “disappearing” if you debit but fail to credit due to a crash |

| Consistency | Transactions move the DB from one valid state to another, respecting rules | Order total must equal the sum of its line items; foreign keys must point to real rows | Rows that violate business rules, like orders with totals that don’t match their items |

| Isolation | Concurrent transactions behave as if run one after another | Two users updating the same inventory count don’t overwrite each other’s changes unexpectedly | Race conditions where concurrent updates see half-finished data or lose each other’s work |

| Durability | Once committed, data stays saved even if the system crashes | A completed purchase remains recorded after a power failure | “Ghost” operations that appear to succeed but vanish after a restart |

In practice, you usually experience ACID through a transaction API: you begin a transaction, perform several reads and writes, then either commit (if all went well) or roll back (if something failed). In an interview, tying each property to a story - like how a transaction protects a multi-step order placement or a complex user signup flow - shows you’re not just repeating definitions; you understand the kinds of bugs ACID is designed to prevent.

AI assistants are good at generating the raw SQL or ORM calls to perform individual updates, but they won’t automatically wrap related operations in a transaction or pick an appropriate isolation level. That part is on you. A strong interview answer might explicitly say, “If I use AI to draft the data access layer, I’ll still ensure multi-step operations run inside transactions so they’re atomic and durable, and I’ll test concurrent scenarios to make sure our chosen isolation level preserves consistency without killing performance.” That’s the kind of transactional thinking hiring managers are looking for when they ask about ACID under interview heat.

How database indexes work

Database indexes are like the index at the back of a cookbook: you can either flip through every page to find “chocolate cake,” or you can jump straight to the right page via the index. When interviewers ask how you’d optimize a slow query, they’re really checking whether you understand this core idea and can use it deliberately. Modern system design and database rounds, including those described in talks like The 2026 Dev Stack: Coding + AI, consistently treat indexing as a foundational performance ingredient rather than a nice-to-have.

A database index is an extra data structure (often a B-tree or similar) that the database maintains to make certain lookups fast. Without an index on a column, a query like SELECT * FROM users WHERE email = 'x' may require a full table scan, checking every row. With an index on email, the database can jump directly to matching rows using the index, then fetch the actual records. Indexes are especially powerful for columns used in WHERE clauses, JOIN conditions, and ORDER BY/GROUP BY operations.

| Query pattern | Without index | With appropriate index | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lookup by unique field (e.g., email) | Full scan of all rows | Fast point lookup via index | Extra write cost when inserting/updating emails |

| Filtering + sorting on same column | Filter all rows, then sort in memory | Use index to both filter and read in sorted order | Index must match sort direction and column order |

| Join on foreign key | Nested loops over both tables | Use index on foreign key to find matches quickly | More indexes to maintain as relationships grow |

| Ad-hoc analytics on rarely-used fields | Occasional full scans acceptable | Index may sit mostly idle | Wasted space and slower writes for little benefit |

The catch is that indexes aren’t free. Every index you add consumes extra storage and makes writes (INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE) more expensive, because the database must update the table and each affected index. Too many or poorly chosen indexes can actually slow the system down. That’s why a good interview answer includes how you’d identify the right columns to index (looking at real query patterns, using tools like EXPLAIN plans), and how you’d periodically review and drop unused or redundant indexes.

AI tools are surprisingly good at suggesting “add an index on this column” when you paste in a slow query, but they can’t see your entire workload or storage constraints. In an interview, it’s worth saying you’d use AI to brainstorm potential indexes, then you’d validate each suggestion by checking query plans and measuring performance before and after. That shows you treat indexes as a deliberate performance ingredient - carefully chosen and tested - rather than seasoning you just dump on the database and hope for the best.

Sharding and when to use it

Sharding is one of those concepts that sounds glamorous in system design interviews, but in real life it’s more like rebuilding your entire kitchen while still cooking dinner every night. Interviewers bring it up to see if you understand that it’s a last-resort scaling strategy, not the first thing you reach for. System design-heavy question sets, like the full stack scenarios collected by CodeSubmit, often mention sharding alongside caching and replication to test your sense of “scale this sensibly.”

What sharding actually is

Sharding is horizontal partitioning: you split a large logical database into multiple smaller databases (shards), each holding a subset of the data. Instead of a single users table with 500 million rows on one machine, you might have ten separate databases, each with 50 million users, partitioned by user ID range or region. The application (or a routing layer) decides which shard to talk to for a given request, usually based on a shard key like user_id or tenant_id.

Sharding helps when a single database instance can’t handle the workload even after you’ve scaled it vertically (bigger box), tuned queries, and added indexes. By spreading reads and writes across multiple machines, you increase total capacity and can keep individual shards small enough to fit comfortably in memory, which improves performance.

| Scaling strategy | What it does | Complexity | When to consider it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical scaling | Give one DB server more CPU/RAM/disk | Low | First step; when current box is underpowered but not maxed out yet |

| Read replicas | Add follower DBs for read-only queries | Low-medium | Read-heavy workloads where master is the bottleneck |

| Caching (e.g., Redis) | Serve hot data from memory instead of DB | Medium | Hotspot reads, expensive queries, frequently accessed reference data |

| Sharding | Split data across multiple DBs based on a key | High | Very large datasets or sustained high throughput after other optimizations |

Trade-offs and what interviewers listen for

Sharding buys you scale, but at a price. Cross-shard joins and transactions become tricky or impossible; you may need to denormalize data or move some logic into the application. Rebalancing shards as certain ranges grow faster than others can be painful. In an interview, you’ll earn more points by saying “I’d try vertical scaling, indexing, caching, and read replicas first, and only then consider sharding when we truly outgrow a single primary” than by jumping straight to “We’ll shard by default.” That kind of answer lines up with how experienced engineers describe sensible growth paths in full stack career guides like the system design discussions in Coursera’s web dev interview prep.

AI tools can definitely help you sketch shard keys, routing logic, or migration scripts, but they don’t automatically understand your access patterns or failure modes. In an interview, it’s worth saying you’d let AI assist with boilerplate and “what if” experiments, then you’d still own the hard parts: choosing a shard key that avoids hotspots, planning a migration that keeps the app online, and deciding whether your team is ready to handle the operational complexity. That’s what convinces an interviewer you know when sharding is the right ingredient - and when it’s overkill for the dish you’re actually cooking.

Data model for a social feed

Designing the data model for a social feed is a favorite system design question because it forces you to juggle relationships, query patterns, and performance under pressure. You’re basically being asked, “How would you store posts, likes, and relationships so we can build a fast, personalized feed?” Articles on modern interview expectations, like the AI-era breakdown on Medium’s coverage of technical interviews, call this out as a classic way to test whether a candidate can think beyond simple CRUD.

Relational model for core social data

In a relational database, you typically normalize the core entities and use foreign keys to keep things consistent. A common starting point looks like:

| Table | Example columns | Role in the feed | Key indexing choices |

|---|---|---|---|

users |

id, name, email, created_at |

Who can create and see posts | Index on email (login) and maybe created_at (analytics) |

follows |

follower_id, followed_id, created_at |

Defines the social graph (who sees whose posts) | Composite index on (follower_id, followed_id) for fast follow checks |

posts |

id, user_id, content, created_at |

The actual items in the feed | Index on (user_id, created_at) for “user’s posts” queries |

likes |

user_id, post_id, created_at |

Engagement signals for ranking or UI | Index on (post_id, user_id) for like counts and “who liked” queries |

To build a user’s feed, you’d fetch the set of people they follow from follows, then get recent posts from those users (possibly via a join or an IN query on user_id, ordered by created_at). As you talk this through in an interview, mention where you’d denormalize (for example, storing a like_count on posts and updating it asynchronously) and where you’d add indexes to keep feed queries fast.

Document-oriented or hybrid approaches

In a document store like MongoDB, you have the option to embed some data (like recent comments) directly in a post document or keep separate collections for users, posts, and follows. A common pattern is to still normalize core entities but denormalize the “feed” itself: precompute timelines or per-user feed documents that list post IDs in order of relevance. That reduces query complexity at read time but increases write complexity when someone posts or follows a new user. In an interview, it’s helpful to say you’d start with a normalized relational model for clarity, then consider document-style denormalization or a dedicated “feed” store once performance or scale demands it.

Feed generation, performance, and AI’s role

Once the schema is sketched, interviewers usually push into performance: would you generate feeds on read (calculate them when the user opens the app) or on write (fan out new posts into followers’ feeds as they’re created)? You might answer that a simple version uses “fan-out on read” for small systems, then moves toward “fan-out on write” and caching as the user base grows. AI tools can definitely help here: you might ask a model to propose SQL queries for “get N latest posts from people I follow” or to suggest index combinations. But your job in the interview is to sanity-check those suggestions, explain how your data model supports the queries you care about most, and describe when you’d introduce denormalization or caching to keep that feed snappy as the app - and the heat - scales up.

Designing a URL shortener

Designing a URL shortener is a classic system design interview dish: small enough to tackle in 30-45 minutes, but rich enough to show how you think about APIs, data models, performance, and scale. It shows up over and over in full stack question banks, including system-design sections in resources like CodeSubmit’s full stack interview scenarios, because it forces you to connect frontend, backend, and database choices under time pressure.

Clarifying requirements and basic API design

Before writing any code, you’d nail down what the “judges” are actually asking for. A simple version usually needs to:

- Accept a long URL and return a shortened code (for example,

https://sho.rt/abc123). - Redirect users from the short URL to the original long URL quickly and reliably.

- Optionally track basic analytics like click counts or creation times.

From there, you can propose a minimal HTTP API:

POST /shorten→ body includeslongUrl, response includesshortCodeand full short URL.GET /:code→ looks up the original URL and issues an HTTP redirect (301/302).

Explaining these endpoints clearly, including status codes and basic validation (e.g., rejecting invalid URLs), already demonstrates you’re comfortable designing user-facing and programmatic interfaces.

Core data model and request flow

Next, you map out how data moves through the system. A simple relational schema might look like a single urls table, while a NoSQL store would have a similar mapping concept:

| Component | Example structure | Responsibility | Key considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data store | urls(code, long_url, created_at, click_count) |

Persist mapping from short codes to long URLs | Index on code for fast lookups; keep code unique |

| Shortening service | API layer handling POST /shorten |

Validate URLs, generate unique codes, store mappings | Collision handling, rate limiting to prevent abuse |

| Redirect service | API/edge layer handling GET /:code |

Resolve code to long URL, redirect, update analytics | Low latency, avoid DB round-trips when possible |

For the short code itself, you might describe using a base-62 encoding of an auto-incrementing ID, or a random string with collision checks. In an interview, walk through the lifecycle: request hits POST /shorten, URL is validated, code is generated and stored, then GET /abc123 looks it up and redirects while incrementing click_count (either synchronously or via an async job).

Scaling, caching, and reliability

Once the basics are clear, interviewers usually “turn up the heat” by asking how you’d scale. This is where you talk about:

- Caching hot codes: Store popular code→URL mappings in an in-memory cache (like Redis) or at the CDN/edge to avoid hitting the database on every redirect.

- Read-heavy optimization: Use a load balancer in front of multiple redirect servers; add read replicas for analytics queries if using SQL.

- Write patterns: Ensure unique code generation at scale (e.g., using ID ranges per node or a central ID service) and plan for collision handling.

- Resilience: Decide what happens when the DB is down - do you serve from cache, show an error, or degrade analytics updates gracefully?

System design prep guides, like the ones referenced in Coursera’s web dev interview prep resources, encourage candidates to layer these concerns gradually: start with a single app + DB, then add caching, replication, and only discuss sharding if traffic and data volumes truly demand it.

Using AI as a helper, not a crutch

AI tools can absolutely help here. You might ask an assistant to draft code for the POST /shorten handler, sketch a database migration, or propose a base-62 encoding function. In an interview, though, your job is to own the architecture: choose a collision strategy, decide where to cache, explain how you’d prevent abuse (rate limiting, basic auth for the API), and reason about failure modes. If you can do that out loud while keeping the design simple and incremental, you’ve shown the interviewer that you can run the kitchen - even if an AI sous-chef helps you chop some of the vegetables.

Designing a real-time chat app

Real-time chat is a go-to system design prompt because it cuts across the whole stack: frontend state, WebSockets, backend routing, persistence, and scale. It shows up regularly in modern interview prep, including real-time focused scenarios discussed in pieces like Final Round AI’s coding interview tools guide, precisely because it forces you to reason about both user experience and infrastructure under time pressure.

Clarifying requirements and choosing the transport

Before diving into databases, you’d start by clarifying what “chat” means for this system. A solid baseline usually includes:

- 1:1 conversations and group chats.

- Near real-time message delivery with typing indicators or “online” presence.

- Reliable message history that survives refresh and reconnects.

Then you’d pick a transport. For real-time, low-latency updates, WebSockets are the default choice: they give you a persistent, bidirectional connection between client and server. You might mention that you can fall back to long polling or Server-Sent Events in constrained environments, but that WebSockets are the “main course” for interactive messaging apps.

Core components and how they fit together

To keep your explanation structured in an interview, it helps to break the system into a few clear components and talk through how a message flows from one user to another.

| Component | Role | Key data | Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Client (web/mobile) | UI for sending/receiving messages, showing presence | Local state: current conversation, message list, connection status | Reconnect logic, optimistic UI, handling out-of-order messages |

| WebSocket gateway | Maintains active connections, authenticates users, forwards events | In-memory map of user → connection(s) | Horizontal scaling, sticky sessions or shared state, auth on connect |

| Chat service / API | Business logic: validating, routing, persisting messages | Conversations, messages, memberships | Backpressure, idempotency, delivery guarantees |